The Princess of Manoa

|

The Princess of Manoa

It was at the head of this valley that long ages ago Hine, spirit of the rain-clouds, and Kani, her husband, who was god of the winds, came to live. They had one child, Kaha, a young maid whom all the gods loved, and whom the great and powerful god of the sea had asked for, to be the wife of his son, Kauhi, prince of the sea. But Kaha was only a happy sprite who cared not the least for Kauhi, but who loved best of all a swift flight in the cloud-chariot of Hine, when, driven by the winds of Kani, it skimmed over the shining green earth and far out above the blue ocean. It was such fun to spy out the little grass huts of the earth-folk, and pour down swift gusts of rain, just to see the people scurry to shelter. One day, however, scudding so low that the clouds almost caught the tree tops, they met a breeze just in from the sea, and stopped a moment above a group of young earth-folk who were dragging their sleds up a long, smooth, grassy hill, and making the walls of the valley ring with their laughter. "Oh, wait, mother, wait! I must see what they are going to do!" she begged "Not now, dear, we will spoil their sport if we stay. See, their sleds are wet already." As they passed on, a wild shout came up to them from below, and the little air princess, looking back wistfully, saw the whole merry company speeding, with the swiftness of the wind itself, down the slope in the bright sunshine; and for the first time she felt that she was well, she did not know exactly what, it was so new a sensation, but somewhere inside of her there was a queer place that felt like a hole. Many times after that she caught distant glimpses of them, but one day she pleaded so hard that Hine stopped her chariot above the hill where the earth-people were eagerly discussing the fine points of the young chief's new sled. Down poured the rain, quenching their laughter and drenching their sleds, while their brown shoulders shone in the wet like polished bronze. What happened next made the air-child know that there was something within her that had never been there before, for the young chief throwing back his fine head until his eyes looked straight up into Kaha's though that he did not know shook his clenched fist at the cloud; and then, startled at his own daring, turned and sped to cover after his companions. Poor little Kaha! She had just been thinking how much finer he looked than Kauhi who wanted to marry her some day. Back in her home on the high mountain peak, there was still something so odd about Kaha's eyes that the air-people asked what had happened Hine knew, and wisely said nothing ; but she took Kaha and retired to the other side of the great mountain, and for a long time the little valley of Manoa parched in the hot tropical sun, and the waterfalls, that had always been so noisy and rollicking as they leaped from the rocks, shrank to tiny streams and almost dried up. The air was so still that not a leaf in all the valley stirred ; the heat rose in blue crinkles even to the tops of the cocoanut trees, and the earth-folk went about slowly with heavy eyes and parted lips. But the other side of the great peaks was dark and dreary. Kaha missed the sunshine ; she shivered in the damp mountain shadows and grew listless and sad The air-folk gathered together and told their wildest tales to amuse her; but though she tried hard to please them, her pitiful little mouth would droop instead of smile. Sometimes she did not even hear them so intently was she listening for some sound from the valley. Then one day a wonderful thing happened! She was sitting on a high rock looking longingly down into Manoa when a great cloud, dense and dark, gathered about her, shutting her in alone, and blotting out the sky, the mountains, the valley. She thought she heard sobs and a low moan that sounded like a farewell, and she called out, but her own voice was deadened by the thick mist Presently the cloud moved, she felt herself lifted from her seat, and gently borne down, down, until her feet touched the earth. Wonder of wonders ! She stood a little brown earth-maid with scarlet flowers in her long black hair. Her dress was of the finest and softest tapa; around her waist was a girdle woven of the tiniest iridescent shells; while clasping her neck and smooth arms were many strands of the same brilliant gems of the sea. She stood a long time, dazed, for the earth looked so different now that she was really on it. The trees were taller than she had thought, and the grass softer. She took a few steps ; a delicious new sense thrilled up through her little bare feet and filled her why, what was this she almost felt now for the first time? something within her that seemed to hold more joy than she ever had known before. So she tripped on over the springy grass singing a song quite new to her, singing in a voice that sounded at times like the sweetest whisper of the wind, and again like the gentle patter of raindrops, until she found herself close to the very group of young earth-folk she had so often watched from above.

Startled, they all gazed at her in silence the sons and daughters of the lesser chiefs because they did not dare to approach, unbidden, one whose dress and ornaments proclaimed her of the most exalted rank. But Mahana, son of their great chief of chiefs, he who had dared to shake his hand threateningly at Mine's chariot, why did he not speak? Mahana stood bewitched He had never seen any one so beautiful, and his heart pounded so at the roots of his tongue that he could not speak. And Kaha, looking shyly at Mahana, thought, "Yes, he is braver and more beautiful than Kauhi, son of the sea-god" At last, the young chief remembered his manners, and bowing low before her, said: "Shame on my father's people that we treat a stranger so discourteously. Will you not join us? If you have come from the other side where the mountains are like walls of rock, you have never known the pleasures of our hillsides. What shall we call you?" "I am Kaha, and I come from there," pointing to the mountains. "May I go, too? I have always wanted to, but ' and then she stopped, afraid that if she told them that she did not truly have a beautiful, brown, satiny skin like theirs, they might not like her; and their bright, laughing black eyes and red lips seemed to her most desirable. Mahana swung his long sled of polished wood in front of her, and said, almost breathlessly, for he was still somewhat confused: 'You have come a long way. My sled shall carry you to the top." But Kaha, laughing, was half-way up the hill before he could overtake her, and they walked on shyly together, eager questions burning on Mahana's tongue, but on his lips only words of courteous hospitality. When it came to seating herself on the sled, Kaha was a little awkward at first, but that was not surprising, and no one seemed to notice. When all were ready Mahana gave his sled a sudden push and sprang on behind her. Down they sped over the shining grass, faster and faster, until the blood fairly tingled in her veins, and her long black hair whipped across the lad's brown shoulders. The young chief's sled went faster and farther than any of the others. It was far beyond the foot of the hill when he skilfully turned it into the shade of a wide-spreading tree. Kaha's cheeks glowed like crimson roses under a creamy-brown veil, and her eyes shone with glinting lights that danced in rhythm to her rippling voice, while they sat a moment to breathe before the upward climb. Again and again they flew, breathless, down the long hill ; again and again they climbed it to the music of happy laughter. Once Kaha heard her father's whisper in the wind that stung her face; at another time she looked up and threw a kiss to a cloud sailing slowly overhead; but she did not want it to come for her, not yet "Once more we will ride our sleds," Mahana said at last, "then we will return to the feast at my father's house." But he whispered in Kaha's ear, "You will come, too, Kaha, and later, when your people come for you, my father will treat with them, and you shall stay; for a chief's son must marry, as you know, and I would rather have you for my wife than any one I have ever seen." "If they will not, what then?" and Kaha's eyes laughed teasingly. "'Then we shall fight," said Mahana, his flashing eyes, his broad chest and his straight limbs burnished brown in the sunshine, making him quite as fine to look at as any god could possibly be. Down the hill they flew again, but this time Mahana gave the sled such a vigorous push that it sped away out across the plain and down another hill before it stopped out of sight of all the company. Kaha tried to rise but could not ; her knees shook and she was afraid, for now she knew she must confess and go. Fear was a new sensation to her, and showed how very nearly like a mortal she was growing. She sat still on the sled until Mahana leaned over, and taking her by the hands, raised her to her feet and kissed her. Then the little maid knew what had happened to her; that the air-spirit in her borrowed body had become a mortal soul, and that she could never go back to the clouds again. A splash of rain fell on the hand Mahana still held, and she looked up to the clouds rolling heavily overhead Soon great drops were falling swiftly but gently all about them, while the wind moaned,with a new note of sadness, through the long grass. But Kaha was a spirit no longer, and she let Mahana take her in his arms while she told him, as well as she could for the sobs that choked her, who she was and how she had come to him. When she had finished, Mahana raised his face to the sky, and stretching out his arms with his palms turned upwards, chanted a vow to the gods for their great gift. When he led Kaha before his father and the nobles of the court, there was a new dignity and stateliness in the boyish figure. He stood a moment, searching in his mind for the right words with which to present the girl. Kaha, though very shy and rosy, was quite self-possessed again, and wonderfully beautiful, so beautiful that before Mahana spoke she had won for herself the favor he would beg. "As you commanded, my father, I have chosen my bride. I give her to you until the time is right for our marriage." And the great chief answered: 'You have chosen well." So Kaha went to live in the big house that was so beautifully woven of grasses. At first she was the great chief's beloved daughter, and the daughters of the lesser chiefs were her maids of honor and companions. Soon she knew all the brave deeds of the great warriors, and wove them into such sweet melodies that the people came from the mountainsides and up from the seashore to listen to her wonderful songs. She learned to swim in the deep pools under the waterfalls at the head of the valley ; she could dive from the highest rocks into the dark water, and come up on the farthest side, laughing and shaking her thick hair from her eyes. She knew where to find the fine matte, and how to twist it into fragrant leis; and every day she wove the brightest flowers into garlands for the great chief and Mahana. At first, when they went down to the sea to watch the fisherman and to gather seaweed for the feasts, she kept well within the reef where the water was shallow and clear, for she remembered Kauhi, son of the sea-god, and feared his power; but as the dreamy days went by in security, her other life slipped into the dim past, and she almost forgot him. But always when it rained she bared her head to the drops, and always she turned her face into the wind to feel its caress on her cheeks. After a while she became Mahana's wife. Then one day the great chief said that the time had come when Mahana should be made a chief in his own right; that he would give a feast that should last a whole week, and that all the nobility of the island should attend, to honor the young chief and his bride. Kaha called her maids and went singing down to the sea to gather seaweed for the feast. The water was so clear and still that they could see every tiny shell and branch of coral, and they plunged in fearlessly. Farther and farther from the shore they wandered in the shallow water, picking only the finest and rarest of the sea plants, until they came to a break in the reef where the water was deep, and a channel opened out to the ocean. I will swim across," Kaha said, for the best of all are on the other side." She sprang into the channel, but had only taken a few strokes with her strong, young arms when the black fin of a shark cut the waves. It disappeared, and a moment later a white shadow shone in the blue depths; then it sank out of sight again, but Kaha, too, was gone. Terror-stricken, the women rushed up the valley. The men heard their cries and came out to meet them, and they turned back to show the place where Kaha had disappeared; but when they came to the shore again they found her body on the sand The wailing could be heard far beyond Leahi, and Mahana, beating his breast, cried aloud: "It was Kauhi, son of the sea-god, who did this deed!" And Mahana was right Always on the watch, Kauhi had seen her in the water, and, quickly taking the form of a shark, had caught her and carried her away, meaning to restore her to her own people of the air. But Kaha had become mortal, and he soon found that it was only the little drowned body ot a Hawaiian girl that he held Sorrowfully then he carried her back, near to the shore, and, when a long wave rolled in from the sea, he laid her on its crest, and sent her on to the yellow sand Tenderly they took the little girl up and wrapped her in the finest tapa, and in the glistening leaves of the ti plant, which, every one knows, all evil spirits fear more than anything else ; and they laid her in a grave in the heart of the green valley she loved. For long years Mahana and his people mourned her; then, one by one, they, too, died; but Hine, spirit of the rain, and Kani, god of the winds, still weep and mourn about the spot where their daughter was buried.

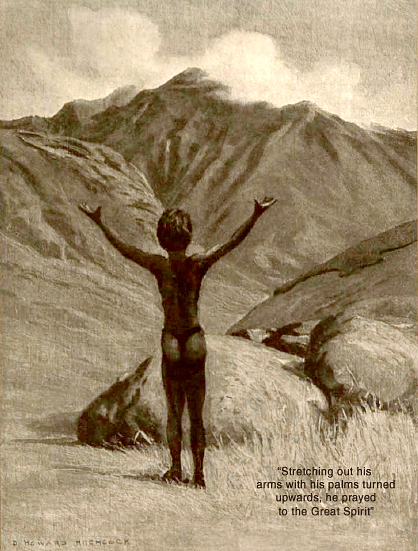

And to this day when the rain splashes on the sleds of the children of Manoa, they look up and exclaim impatiently, "Oh, there comes Hine with her tiresome tears!" Back to Contents

N the most ancient of times, when the eight islands themselves were new, two children once sat on a rock of the great dark mountain, almost on the edge of the precipice that drops sheer to the floor of the valley below. "Do you think, Mana, that our father will soon return?" asked the girl. Her pretty lips drooped at the corners, and two big tears overflowed" her dark eyes. He has been gone less than a moon yet, and war is long. Some of the warriors never return," answered the boy. His teeth closed till they ground together, and down the little girl's face the tears rolled thick and fast. "I think they want to kill us," she sobbed. "I tried I did try to beat the tapa right, but holes would come in it ; I couldn't help it ! We never worked so in the days before our father went away. She she snatched the stick out of my hands and hit me with it many times. My arms are bruised and sore, and my head aches." The child sobbed desolately. The boy sprang to his feet and strode to the edge of the precipice, turning his back toward his sister for the first time since the morning. "Mana!" she exclaimed "Again, today?" There were burning welts across his back, and she laid her cool hand on them. He turned quickly, his face lowering with shame and anger. Yes, Umi is a man grown, and powerful, but I shall be a man some day, too!" his hands clenched threateningly. 'They are fiends! they are devils this sister of our father and her ugly son ! They mean to kill us while he is away so that Umi will be the young chief of Waialua; then they will tell some smooth tale to account for our disappearance." a threatening voice called. The girl sprang up trembling. "She will beat me again. She said she would if I did not finish the tapa before the sun slept, and I couldn't" "Noe!" called the shrill voice again, this time nearer. "Come," whispered Mana suddenly. "She shall not beat you again! The mountains are kinder than they. Come." Grasping his sister's hand he drew her into the shadow of the bushes where they crouched, scarcely breathing, till the woman passed; then aching, sore and desperate, they stole away down the farther slope of the mountain toward the pale star of evening. The next day the sun was sinking close to the edge of the world when the two runaways, tired and spent, dropped on the sand at the foot of Leahl Noe leaned her head against the warm rocks, tears creeping slowly from under her long lashes. "Don't, Noe," Mana begged gently. "We're tired and hungry, of course ; but many times it has been so with us since our father went over the sea, and we were beaten and tormented besides. Rest here in this shelter while I go down to the shore. There are fish in the pools among the coral; I can see them, and the limu beckons to us from the wet rocks. We shall eat before the night falls." Noe winked the tears from her eyes, and sprang up smiling. 'Then I shall go, too," she said, "for many hands make a quick feast." Together they ran down to a cove in the rocks, where the waves ebbed and flowed over the dark, ragged coral, and the seaweed waved its juicy fronds in the shallow water. Soon Mana picked up a struggling fish on the point of his spear, and when, presently, it lay on the glowing coals of a fire, Noe returned with a net full of seaweed and tiny shell-fish. Since they left the mountain they had eaten nothing but a few half-ripe berries, and the white flakes of the steaming fish and the brown limu were more delicious than all the luxuries of the king's feasts. On the white sand among the warm, dry rocks the children stretched their tired bodies in drowsy comfort, while across the darkening water the moon flung a path paved with broken chips of silver, and over it the stars beckoned to golden dreams. They were happy again, almost as happy as they had been before their father sailed away with the king to make war on another island, and left them to the care of his ambitious sister. By day they fished or raced over the white sand of the beach; at night they slept under the open sky. But one morning when the dawn waited just beyond the shadow of night, and the late moon cast a pallid light over the land, Mana suddenly awoke. On the beach stood Umi looking down at their fish-net spread to dry on the sand On his evil face was a triumphant smile, and his long cruel fingers were spread in anticipation. Stealthily arousing his sister, they crept, crouching in the shadows of the rocks, up over the hill into the shelter of the forest where they lay concealed among the thick ferns and vines, creeping out only now and then to gather a few berries and wild fruits. When, however, day after day passed in peace they took courage again. The season of rains was near, and Mana built a cabin of dried grasses, while Noe gathered the long, shining leaves of the hala and wove them into mats for the beds. They planted a garden, and Mana set snares in the forest for game. Months passed in security, and they began to laugh aloud again. One evening they sat before the door of their hut, Mana playing softly on his bamboo flute, and Noe chanting low the song of their great ancestor, the rain-god. Slowly the sun sank into the ocean, and the star of evening shot a cold shaft of light through the warm afterglow. Mana laid down his flute and spoke. "In three days, my sister, we shall gather the roots of the taro. We shall be rich now, for the garden flourishes, and we have many mats and calabashes." "And better yet," answered his sister, "we work without bitterness." But that night they awoke with a fiendish laugh ringing in their ears, and the hot breath of flames scorching their faces. Stealing out of a little opening in the back of the hut they fled deeper into the forest. Within the shadows of the big trees they turned and saw, in the glare of the burning thatch, the huge, distorted figure of Umi furiously laying waste the garden. In terror they ran through the woods, tripping among the tangled vines, falling over loose stones, panting, sobbing, no retreat seemed safe enough. For weeks they wandered, sick at heart, hungry, worn, now driven to the mountain heights by the taunts of their foe, now fleeing to the plains to escape the echoes of his jeering laugh as he followed. Then came the season of the great waterfamine, when Hine called the clouds to the other side of the great dark mountain, and the ground of the plains opened ragged lips beseeching the blazing sky for rain. Grass seered brown in the scorching winds, and the leaves crisped and fell from the branches, till the naked rocks were exposed like gaunt bones through the rags of a beggar. At last Umi drove the children down the parched valley to where the mountains open out to the sea, and left them there to die. About them spread dry rolling hillocks sparsely covered with coarse grass and a few straggling berry bushes. The sun beat on their unsheltered heads, their lips dried and cracked with thirst; and in Noe's dark eyes there smoldered the fire of a consuming fever. "What is the use," she muttered dully, "of planting and weaving, of cutting and polishing calabashes, and beating the tapa, only to have them turn to ashes before our eyes? My head throbs and grows dizzy at the thought, and see how your hands, the hands of the son of a great chief, are worn with the heavy toil!" Mana sat on a sun-baked rock, his heart sore with bitterness, and Noe lay whispering to herself with her eyes closed. He changed his position so that his shadow fell across her face. "Noe," he whispered, bending anxiously over her, "littie sister, what are you saying?" The dull voice only babbled on unmeaningly. "Noe!" the boy called, his voice sharp with a new fear, "wake up ! You are having a bad dream. Wake up!" Suddenly Noe opened her eyes glittering with fever and delirium. " Water!" she called hoarsely, "Water, I tell you! "But there is no water," Mana sobbed miserably. Noe beat her hands into the hot grass. Mana shook her, calling her name frantically, and she laid back again, muttering softly with her eyes closed. Frightened and desperate the boy sprang to his feet, facing the mountain where the gray draperies of the great rain-god lay on the dark peaks. Stretching out his arms with his palms turned upwards", he prayed to the Great Spirit.

"Father of our fathers," he cried, "God of the blessed waters, turn your eyes toward the unhappy children of your children ! Send us the life-giving medicine, or my sister will die." High up in the mountains the clouds stirred, then gathered thick and dark over the pool at the foot of the waterfall. Out of the mist rumbled the deep voice of the water-spirit, and the call awoke Moo, the great green lizard, from his long sleep in the earth. He stretched himself, and listened. When the voice of the spirit ceased, Moo slipped into the pool, and burrowed under the spur of the mountain, down under the foothills, under the hot hillocks, and the dried stream-bed, through to the place where lay the sick child. With a lash of his powerful tail he broke open the rocks, and the water, following him through the newly made tunnel, gushed out crystal-clear, filling the stream full to overflowing. Mana, crouching with his face buried in his arms, heard the gurgle of the water and sprang to his feet. Deep and cool spread the pool before him, and on down through the parched fields rippled the little stream. And by and by where it ran new life sprang up. The straggling bushes burst into luxuriant bloom, and the berries grew luscious and sweet The soaring birds heard the splash of the water, and dropped on stilled wings to drink at the margin. And there the warrior-chief found his children. But hardly had the salt dried on his canoes ere they were launched again, this time to carry the wicked woman and her son into exile on the Island of Demons. But the spring still flows from the rocks, the Well of Last Resource, to the people of the valley. Back to Contents

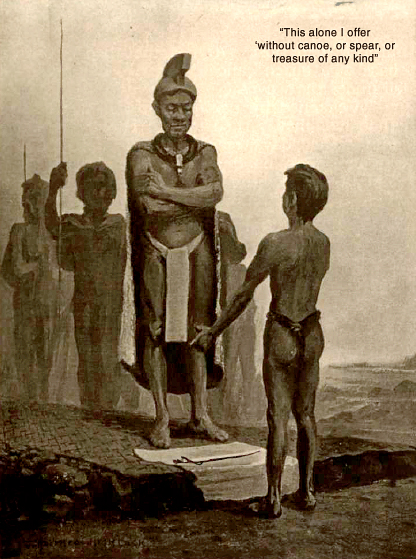

HE king stepped from his canoe to the beach, and his keen eyes, roving the sea, saw a dark head rising and felling with the waves far out from the shore. It was then but a speck on the broad blue ocean, but so swiftly it approached that he waited among his chiefs, watching and marveling at the force that lifted the sinewy body half its length out of the water at each stroke. Even then they saw that the man carried a long spear in one hand, or drove it before him across the smooth stretches between the waves. At last the swimmer rose to his feet in the shallow water and strode up the shore. He was naked, lean, and lithe; and his wet brown skin shone in the sun like polished koa. There were wounds on his arms, and a deep ragged gash across his chest, but he stood erect in the royal presence, and when the king spoke he answered unafraid. "From Moku Ola, I come. A day and a night in the sea." "From Moku Ola!" exclaimed an old chief in surprise. "From the City of Refuge." "And who is the youth who comes thus boldly from Moku Ola to Waipio?" asked the king. "Kuala, am I, son of Laa who is dead through the treachery of his brother. Seven days ago the battle was fought, and when I sought my father among the slain I found him with his dead arms locked about his living foe. Sons of one father were they, but the clasp of death was stronger than had been the living bond Then came the son of my father's brother, great of stature, and powerful, but with all his strength he could not undo the embrace. He called for help "And where was the son of the dead chief?" asked" the king. "I stood beside them, looking on." The youthful face was grim and scornfuL "And then?" the king's eyes gleamed under their heavy brows. 'The day after the battle my father's brother, who was too weak from his many wounds to leave his couch, sent for me ; but I was searching the battle-field and did not go. The next day he came to me, and offered me a part of my father's land, and a place in the household he had stolen." "And, boy, what did you answer?" asked the great warrior. "I have yet to answer," said Kualu. "At that moment I found what I sought my father's spear, and it grazed the cheek of our foe before I scarce knew it had been in my hand" "Go on," said the king with savage interest "His son sprang upon me, but my javelin was a stout one. I left him lying on the ground, and fled toward the sea with a half-score of their warriors following me. It was a long chase, and they were net a dozen paces behind when I plunged into the sea, for I had lost much blood in the battle and was weak; but, even as they clutched at my feet, my fingers touched the sacred rock of the Island of Life, and I turned and laughed in their faces." "And what is your desire now?" asked the great chief of chiefs whose valiant heart warmed to the unconquered lad "A place in your service, O king. The reckoning between them and me will come before I lay down my father's spear." And Kualu that day entered the service of the king. It was well known among the chiefs of Hawaii that the king looked with war-like eyes upon Maui, the island whose shores could be seen from Waipio when the waves of the channel rolled unbroken and the sun drank up the mists. But the time of the feast of Lono was near the five days of the year which the gods claim as tribute from the months, and the preparations for the conflict gave place tP the great festival. By day there were games of skill and tests of strength among the chiefs ; music and dancing and feasting in the light of the candle-nut torches filled the long nights; and in the reckless time of the gods Kualu laid aside the memory of his wrongs. But, though the stalwart young chief had looked unflinchingly into the eyes of the great king, in the presence of the king's daughter the hot blood burned in his face, and his tongue clung to his teeth. As a chief of the royal household he saw her many times between the rising and the setting of the sun. When the women sang in the moonlight to the music of the ukeke he heard only the clear tones of her voice, and in the dark of the starless nights he knew the sound of her soft footfall on the rushes. She was a small maid, light as the down of the pulu fern, and as brown, and her dark eyes laughed at his confusion. But the days of the gods were days of greater freedom, and the handsome young chief found that after all the laugh was only in her eyes. On the first day of the new year, when the festival was ended, the king sent his runners over the island to demand a tribute of soldiers and canoes from the chiefs of the outer districts, and the preparations for war went on openly. "Kualu," said the little princess when they met in the moonlight by the spring of Waiamoa, I have talked with Wahia, the Sorceress, and her words are that you will bring back from the war that which shall give you power over kings. We will pray the gods that she be a true prophet." "It is well," said the young chief eagerly, "for I have much to win before the king will listen to us." When, at last, the great fleet of canoes was launched, and the army sailed away, the winds were favorable, and the waves propitious. On the morning of the second day they landed near Lele, where the king of Maui and all his army awaited them. From the first the surge of battle was with the hosts of Hawaii, though fierce and stubborn the resistance; and the conflict raged over the hills till scarce a Maui warrior remained. One band alone held out, strongly entrenched behind a stone wall, and defiant as though possessed of some invincible power. Kualu led the charge over the bulwark, and one by one the brave defenders fell, till, through the thinning guard, he caught the flash of an unknown weapon. Shouting with exultation, he hewed his way into the center of the tumult, and, with a swinging blow of his javelin, brought a strange, white-faced warrior to the ground. As the gleaming blade slipped from the inert hand Kualu seized it, and plunged it to the hilt in the earth; then, with his foot covering the handle, and his javelin dealing fearful blows about him, he stood his ground till the last of the Mauiians were dead, or had fled over the hills. If any save the young chief had seen the strange knife, he had not lived to tell it; and when the army of Hawaii returned to Waipio, the strange weapon was hidden in a bundle of captured spears, and on the tapa covering was the tabu mark of the chief Kualu. In secret he carried it to the cabin of the old seer. "I need your counsel," he said to her in a whisper. "Know you, mother, what I have in this tapa?" He unrolled the covering. "Auwei!" she said softly. "It is the iron knife! But a little while ago a white-faced stranger came to the shores of Maui in a canoe of an unknown shape, and in his hand he carried a knife, the like of which was never seen on all the eight islands : harder than the hardest rock, sharper than the sharpest bone, but thin and bending as the lance of a palm leaf, and with the fire of the noonday sun leaping from haft to tip. They thought he was the white god of whom the prophets spoke, but he died, you say, like any man? The gods have befriended you, Kualu. Leave the knife with me. It is safe here, and there are many who would covet it The time of its power is not yet" While the army still reveled in the glory of victory, the king prepared to strike a blow for still greater power; and from shore to shore, from mountain peak to mountain peak, there sounded the call to arms. By land and by sea the chiefs came with their bands of warriors, till the hills of Hainakolo were covered with camps, and the war canoes lay on the beach from where the first morning light strikes the sand to the last rock burnished by the setting sun. Kualu's kinsmen, both father and son, came by sea with a hundred warriors ; but Kualu bore himself with cold pride, and the feud was buried before the king. But one day when the little princess met her lover at the spring, her eyes were full of tears, and she sobbed as she said to him: "Your kinsman urges me to marry Olapana, his son. He is the most powerful noble on the island and has many warriors, and my mother looks upon him with favor. What shall we do?" Kualu's brows lowered ominously, and he struck his clenched hand on the rock. "Yet Wahia hides the iron knife and counsels us to wait!" he cried passionately. "I am tired of waiting! I have but to lift my hand and a score or more of his warriors will come to me ; then, with the iron knife '"Hush!" said the maid, looking fearfully about. "Wahia says it is a thing of evil. It invites disaster. Also, she says, this war will make great changes; some stars will rise and some will set. Yours is still behind the clouds of the horizon, my chief, but not for long is it to be hidden, Wahia says." But, though the powerful chief pleaded and the queen urged, the king was too intent on his own ambition to consider the marriage of a maid. Never before had such an army put out from any island shore; never before had an island war song rolled from so many throats. The wind brought the sound back over leagues of ocean, and the sea-birds flew to the mountains, screaming with alarm. On the morning when the dawn showed the blue hills of Kauai before them, the king stood on the deck of the royal canoe and saw his fleet spread out over the channel like the wings of a bird so great that, from tip to tip, it measured the width of the island. Kauai lay on the still, blue sea like an enchanted land. Along the shore no canoe broke the placid ripple of the waves; as far as eye could see, neither man nor beast moved on the shore; among the hills no spear caught the flash of the rising sun. All night the strange stillness brooded, but at break of day ten thousand spearsmen poured out of the hills, like a flood through a broken dam, and the impact of the hosts was like the charge of stormy billows on a rocky shore. The air was torn with shouts and cries, with the sound of clashing spears and whirling javelins, and the panting breath of desperate struggle. Suddenly another great army rounded the point by sea to attack and destroy the canoes, and the king sent Kualu to the rescue with a band of picked fighters. They sprang to the boats, and as they cast them off, fleet met fleet with a crash. Men fought on the decks and in the water; foes clenched on the bed of the ocean, and drowned, or rose to the surface to be beaten under again with paddles ; spears and javelins shrieked through the air, till at last Kualu and a score or so of warriors looked at one another across a splintered fleet. "To the king! To the king!" called the young chief; but on the land the battle was lost. The slain lay under the blistering sun, and not one man of all the invading host held out against the defenders. The little band stood aghast before the ruin, until discovered by the foe ; only half of the score escaped. For many days they skirted the coast, trying to learn the fate of the king. At night they landed and crept to the outskirts of the villages, and in the frequent skirmishes five of their number were lost. At last they fled before the chase of a dozen canoes, and two more warriors fell under the waves. Weakened by painful wounds, starved and exhausted, they turned toward Hawaii, and after many weary days reached the island. Though watchers stood on the shore as they drew near, when they landed the beach was deserted Everywhere Kualu found only averted faces. He spoke to the guard before the palace, and the man turned and walked to the other side. He called to a child who had loved him; it ran to its mother, and she covered the little face with her hand. Bewildered and angry, he strode up the valley to the cabin of Wahia. "What is it?" he demanded fiercely. "What evil has worked against me?" The old woman looked in his scarred face ; she lifted his cut and bruised hands, and turned his broad back to the light "The chief Kualu bears not the marks of a coward," she said, "though Olopana returned from the war full seven days ago, and told that you had deserted the king and escaped with all the canoes." Kualu stared in angry amazement at the old woman. He tried to speak, but his throat was choked with fury. "But Kalaunui is not dead," Wahia went on. "Only this morning a wounded spearman returned alone in a broken canoe. He died on the shore, but not before he whispered that the king was a prisoner." With all the old hate stirring in his heart, Kualu returned to the palace. As he crossed the courtyard he passed Olopana and the little prince. They were talking with an old warrior, and near them sat the women of the queen's household; and all but the little lad looked another way. "Turn your young eyes from the sight of a coward, my prince/' Olopana said in a loud voice. The red blood died out of Kualu's face; he turned slowly and walked back to them. No sound came from his rigid lips, but he took the spear from the hand of the old man, and, stepping back a pace, pointed to the weapon in his kinsman's hand. Olopana saw the vengeance in his eyes, and his spear flew wildly, but Kualu waited the space of a dozen breaths, then with a furious blow he buried the spear with the insult in the heart of the slanderer. The days that followed were days of deep humiliation. Taunts showered about him taunts that he resented till his heart was sick with the unending strife. Then one night Wahia brought the iron knife. "The time is come now," she said. "You must go to Kauai and bring back the king." "I bring back the king!" he exclaimed bitterly. "You mock me ! I could not gather twenty men to my standard!" "You have what is more powerful than an army: the iron knife. It is a king's ransom, boy. Take but five men who have proved their faith; be cunning and wise, and you will return to marry the princess, and to hold the highest place in the council of the king." When the canoe with the six young chiefs sailed away from the shore of Waipio, no one but an old woman, and a maid who watched from the shelter of the forest, knew of the treasure that lay wrapped in many folds of tapa in the boat of the disgraced chief, or that he was gone to seek the king. Then the gods gave their favors freely. Fresh breezes filled the sails by day, and at night the canoes rocked in safety on the gentle swells of the peaceful ocean. As they approached Kauai they raised on a spear the emblem of an envoy; and when they landed, the king of the island, surrounded by his chiefs of council, received them at once. Kualu announced their mission boldly. "Victorious king," he said, "we of Hawaii know that our sovereign lives a prisoner on your island." The king gravely bowed. "And we have come to offer canoes and spears, to the number you ask, in exchange for his freedom." "We have more canoes than can find refuge on our shores when the storms sweep the sea," replied the great king with stately courtesy, "and the spears lie in uncounted thousands in the courtyard." "And many of them we should know were we to see them," said Kualu sadly. The next day the six chiefs of Hawaii again asked an audience of the royal council, and added twenty feather cloaks of priceless value to the offer for the king's ransom; and again they were courteously refused. The next day still other treasures were tendered, equally in vain. Then Kualu raised his right hand, and they knew that he had a matter of grave and secret importance to communicate. The attendants fell back, and the King of Kauai and his chiefs each lifted the right hand in token of good faith. Kualu took from under his cloak a long slender roll of tapa and laid it at the feet of the sovereign. Looking keenly about the circle of august faces, he stooped and opened the roll, and the long, thin steel blade lay naked in the sunlight, like a flash of lightning snared. "This alone I offer," he said," without canoe, or spear, or treasure of any kind"

"Auwe-e-e," breathed the council of old nobles. "The iron knife!" whispered the king in awe. "The knife of the white god. Will it buy our sovereign's freedom?" "The king of Hawaii is free," replied the stately old savage. Back to Contents

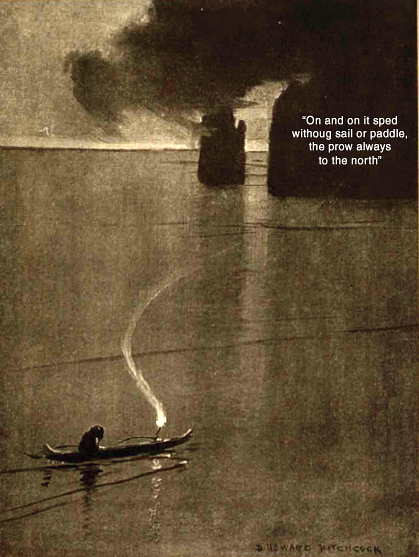

NCE upon a time, many ages ago, that portion of the earth's surface where the blue waves of the Pacific Ocean surge, beating back and forth from the Golden Gate to the land of the Great Dragon, was a desolate waste of arid country, where no green thing grew, and where no bird or beast of any kind had ever been tempted to build a nest or make a lair. It was a region of dreadful mountains towering into the sky, and of hot, sandy valleys between, at least, so some folk say. They ought to know, too, for they are the people who now live on the islands that, in that long ago age, were the tops of the very highest peaks in the middle of that fearful country. An old man who lives in a grass hut on the slope of one of those mountains, up where the mists trail through the tree tops, and the rainbows are forever pointing out treasures of potted gold that nobody ever finds, knows all about it; and for the proof of the truth of this strange tale of his why, there are the mountains and there is the blue rolling sea! Away off to the south, the old man says, where the sky comes down to meet the ocean, was another land where the mountains were giant furnaces of white-hot fire; though waving palms fringed the shores and the hillsides were covered with a glowing carpet of flowers. It was where the gods lived when they were not busy interfering with the affairs of ordinary people. At that time Pele, spirit of fire, was the most beautiful of all the goddesses. Her hair was long and dusky as the cloud of black smoke that poured from the throat of the great mountain; her face was like the flakes of white ash that floated away through the air, glowing rosily in the light of the fire; her eyes were black as the shining lava where it cooled on the edge of the pit The great Kane was her father, her mother was a sea nymph, and though she lived in the heart of the mountains, every day she went down to the shore to talk with her mother. It happened one day when there was great commotion out in the world of mortals, and the gods and goddesses were being so constantly invoked that it did not pay to return between times to their own abode, that Pele wandered alone by the sea. It was a golden morning ; the night haze still lay far out on the water, where the blue of the sea melted into the blue of the sky, and the shadows of the cocoa palms were long on the yellow sands. Suddenly a fleet of canoes broke through the mists, cutting the dancing waves with their thin, graceful prows, and sending the spray in white showers from the points of their sweeping outriggers. On they came, skimming the water like seabirds, paddles flashing in the sun, and a sheen of golden brown bodies swaying rhythmically. Threescore and one canoes in all, spread out like a flock of wild fowl in migrating order ; and the one that led was large and strong and beautiful. Pele retreated to the shelter of a rocky cavern overgrown with ferns and creeping vines, and watched them breathlessly, waiting the tragedy of the reef that no mortal had ever yet survived. Then up rose a figure in the prow of the foremost canoe. From under a shading hand bold eyes searched the coast, found the hidden channel, and the fleet shot through the spindrift and spume of the angry breakers, into the quieter waters within the reef. Straight and tall stood the young chief, the white foam of the fawning surf purring along the sides of the canoe. On his head was a helmet of yellow feathers, and from his shoulders hung a sweeping cloak of the same golden plumage. With strong, swift strokes of their paddles the warriors sent the canoes crunching through the shells on the sand, and beached the fleet high out of reach of the waves. Then the chief threw his great spear, and where it struck and stood upright quivering in the ground, there the guard of honor spread the royal mats. A score or more of warriors began immediately to build the royal lodge of the long fronds of the palm trees woven together; another score set about preparing the morning feast, and a third was picketed about the camp with spear and shield ready to repel a foe, if foe should come. At last the young chief turned and saw Pele standing in the shadow of the rocks, a strange light in her great somber eyes. In a moment he was kneeling at her feet, and Pele saw that he was beautiful as well as strong and brave. She had never seen any one like this bold young chief with the eager eyes and handsome face. For a moment she paused, fascinated; then she turned and fled swiftly up the mountain, Malia following her. Day after day Malia disappeared from the camp for hours at a time, and so successfully did he woo the beautiful goddess of fire, who appeared to him but a simple maid, that she always met him in the cool, green depths of the forest shade. Together they wandered, gathering strange, beautiful flowers or sat on the rocks, Malia recounting his conquests, his long journeys over the vast ocean ; telling of the strange peoples he had warred with, and the treasures he had captured and carried away, while Pele listened with inscrutable eyes. For a long time Malia and his band made their camp on the shore, but at length the soldiers grew restless; adventurers all, they had set out for conquest and wealth, and here there was neither gold nor a people to conquer. Then Kekaha, a goddess whose jealousy of the beautiful Pele made her wicked, took the form of an Amazon, and mingling with the warriors, told them of a wonderful country far to the north, where the gold lay under the open sky, and promised to lead them there. Malia was loath to leave Pele, but the counsel of the lesser chiefs at last prevailed, for one morning when Pele had waited at their trysting-place and he did not come, she wandered on down through the forest, watching and listening. When at last she reached the place where the camp had been, she saw the shore strewn with the disorder of a hasty flight; but the whole fleet of canoes had passed beyond the horizon. Pele sank on the sand, and the wind lifting her long black hair, covered her with it as with a mourning veil. For a long time she sat there unheeding; the fires in the mountains smoldered to a dull glow and almost died out, and still she sat unmoving. Then in the darkness of the night her mother came up out of the sea and spoke to her. "Go, my daughter," she said, "and light a torch at the fire in the great mountain, there is still a spark left. With it search along the coast for a canoe. One of the three-score I capsized, and when the men grew weak with the buffeting and sank to the bottom of the sea, I brought it back to you. Take it and set forth, and I will guide you; but keep the light burning." Pele arose and found the canoe. When she had fixed the torch in the bow and seated herself, a hugh wave rolled up the sand, and, receding, lifted the boat and carried it out to sea. On and on it sped without sail or paddle, the prow always to the north; on and on over the trackless sea, with never a sail in sight; on, until even the seabirds were left behind. At last Pele saw a long black cloud hanging low on the horizon, and under it loomed the shores of a Dreadful Land. Still the canoe sailed on ; the cloud spread and shut out the sunshine, and the air grew thick and heavy. Poisonous vapors floated up from the land, and darkness dense darkness shut down over the whole region.

"Alas," cried Pele, "my boat will be wrecked on the terrible rocks! I can go no further!" Crouching in the bottom of the canoe she covered her face with her hands, waiting the shock of the keel on the shore. When she looked up the land had disappeared. She sprang to her feet, raising the torch high above her head. From the sky on the north to the sky on the south, from the east to the west, the sea rolled. The Dreadful Land lay fathoms deep, and only the tops of the highest mountains rose above the waves, eight rocky islands on the bosom of a mighty ocean. When the canoe grated on the shore of the island farthest to the north, Pele took the torch and climbed to the top. She touched the light to the rocks, and they burned with a flame that lit up every spur and crevice on the mountainside; but Malia was not there. She left the fire burning and embarked again, landing on the island next to the south, where she again lit a fire and searched for her lover, again in vain. From island to island she wandered, until all but one of the mountains were throwing fountains of fire high into the air. As the canoe touched the shore of the last island Pele saw a spear lying on the rocks. "Here will I find Malia," she cried, casting her boat adrift Seizing the torch she sprang from crag to crag, calling in her clear, beautiful voice to her faithless lover. At last she found him, lying dead where the wicked Kekaha had deserted him. Long she mourned on the desolate mountain. Where the torch dropped from her hold it burned a great cavern in the rocks. There Pele made her home. Sometimes she slept, and then the fire died away until only a thin column of smoke floated up from the pit to mingle with the fleecy clouds; when she awoke the whole mountain shook with her restless muttering. She breathed on the smoldering coals, and fountains of red-hot lava shot into the air. Now and then she broke into raging fury, and swept the land with streams of liquid fire that shriveled every living thing in their paths. That was eons ago. One by one the volcanoes on the other islands died out; but to this day in the depths of Kilauea the fire still burns, and the lava surges hot and red. Long ago the fresh sea winds cleared the deadly air; the rain crumbled the rocks to soil. Then the waves of the ocean brought seeds from distant lands, and they took root and flourished; flowers opened to the smiling sky, and fruits ripened in the warm sunshine, until now those dreadful mountain peaks glow with the colors of jewels set in the blue enamel of the tropic sea. Back to Contents

LONE on the lonely sea, in the wide, dark night, a canoe drifted. As it rolled heavily on the sluggish swells, a plaintive chant, weighted with woe, rose and fell with the throbbing waves, and the voice was rich with the pathos of a long past age:

The wail died away in a low moan, and only the wash of the restless sea sounded through the empty night. "The long, long night," the plaint began again.

A child whimpered in the bottom of the canoe, and the woman drew it into her arms and wrapped the thick veil of her long, dusky hair around the little naked brown body. Again the lament floated over the dark water:

Heavy with weariness, the woman drooped over the child and her eyes closed. The canoe rocked deeper on the rising waves; it dipped to the water, and a dash of spray roused her again. She caught up the paddle, and turned the prow of the canoe toward a star hanging low over the sea.

The child had wailed fretfully when it slipped from the mother's arms, and she crooned it to sleep again.

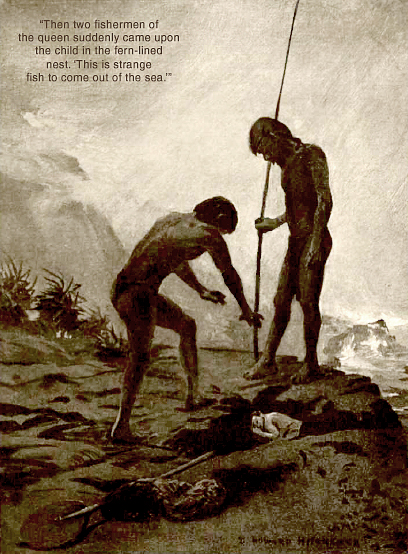

A tinge of gray brightened the line where the sea met the sky ; the day was breaking. But sleep weighed heavily on the woman, and she swayed under the burden; the paddle dropped unheeded from her hand and floated away in the darkness. Still holding the child in a close embrace, she slipped to the bottom of the canoe, and her pain was eased in dreamless slumber ; the child slept in the warmth of the mother's body, and the canoe drifted aimlessly. One by one the stars gathered in their rays and hid in the depths of the blue; the shadows fled swiftly from the face of the ocean, and when the great red sun rose again over the world the canoe still rocked on the empty sea, as it had rocked for many long, burning days. The woman and the child slept on; and the glory of the new day gilded the ocean and the dripping canoe with useless gold The freshening breeze lifted the cloud of dusky hair from the face of the woman, and she was beautiful - beautiful as the dawn, and still in the morning of slim, dainty youth. But while the sun was yet low, a great, dark storm-cloud rolled up from the place of unknown terrors at the back of the sky. The wind struck the water like the flat of a paddle, and the spray leaped high over the crouching waves. With a quick jerk the canoe dipped the water, then rolled back and dipped on the other side. The woman, suddenly aroused, dragged herself painfully to her knees. Already the storm-cloud spread over half the heavens, and the waves, white and broken, fled before the lash of the wind. She looked wildly around for her paddle, and the canoe, unguided, swung its length to the rush of the sea. The child screamed with fright The mother held it close in the hollow of her arm, waiting, for beyond the race of waves towered a mountain of water, its thin edge barely frayed. She braced herself and lay out over the outrigger; but her slender body was like the feather of a sea-bird, and the merciless billow picked up the canoe in its giant's clutch, as though it were but a chip from the hewer's ax, and threw it face down, beating it into the water. When the wave passed on, the canoe lay like a log rolling helplessly in the trough of the sea. The woman came to the surface, still clutching her child, and struck out for the splintered hull Through the long hours of the storm she clung to the slippery wreck, though again and again the sea tore it from her grasp. At last, toward the end of the day, an island loomed dimly through the driving spray, and she left the hull and swam toward the shore. Some time in the blackness of the night she felt the land under her feet ; she dragged herself up the beach, gripping a little limp body in the hollow of her arm, and sank on the dry, warm sand. In the gray of the dawn she roused, but the child lay as she had gathered it to her with the last of her spent strength. Sitting on the sand, she rocked it in her arms, crooning coaxingly with her warm lips on the little cold face. By and by she staggered to her feet, gathered the long grass that grew in the crevices of the rocks above the beach, and made a nest for the little one. "It but sleeps," she said wistfully. "When I return with food it will wake." Then came two fishermen of the queen who had caught nothing that day. "The fish-god is angry," said old Niiu. "He has called them all away." They cast their net again, and drew it in empty. "The queen will eat flesh or fowl this day," said the old man as they strode up the beach. There were footprints on the shore, small, slender molds that dragged at the toes as though the feet had been lifted in great weariness. They led up from the edge of the water to a place where some one had lain long and heavily in the sand. From there the prints were fresher, and the fishermen followed till they suddenly came upon the child in the green nest As they gazed at it in astonishment it moved feebly. "This is a strange fish to come out of the sea," said Niiu. The tiny waif moaned, and he took it in his arms to warm it against his broad chest "Auwei!" he breathed softly in wonder, lifting a slender necklace from the little brown neck. "The child of a high chief! Fish or no fish, I must take it to the queen,"

When Haina Kolo, daughter of a king, dragged her stiffened limbs back to the beach, the fern-lined nest in the rocks was empty. She gazed into it stupified, but at last her face brightened and she laughed gently. "Lei Makani! " she called, and her voice was as sweet as the sound of the waters of Hulawo. She peered among the rocks, but no laughing face greeted her, no shout of baby glee answered; she ran along the beach calling, "Lei Makani! Lei Makani!" coaxingly at times, then again her voice rose clear and loud as the sound of a battle-ax striking the Ringing Rocks. The winds answered, but the child who was named for them was beyond the call. Then for hours she crouched on the shore in the blazing sun, neither hearing nor seeing, till the tide crept up and lapped her feet At the first touch of the water a wild, unreasoning horror leaped into her eyes; she sprang up and ran away from the sea, away from the sight of the rolling billows, away from the sound of the thundering surf, up into the heart of the mountain forest. There she lived for many long years; and in the deep, cool, green shade the peace of the everlasting hills crept into her heart But when the sound of the surf boomed through the hills in the early dawn, and a storm brooded on the ocean, a haunting memory stirred in her half-darkened mind; she would go swiftly down to the shore, and, running along the beach, would call, "Lei Makani ! Lei Makani! " now softly, enticingly, now rousing the echoes with her clear sweet voice. "The mad woman calls the winds," the fishermen would say, and hasten to make ready for a gale. At last there came a season of fierce storms from the south that raged over the land and sea. For many weeks the fishermen dared not venture on the water, and the taro patches were washed away in the floods, so that the people were hungry. It was in the time of the year when the sun hurries across the heavens, and the days are short. The clouds spread over the sky like a thick gray tapa without rent or seam, and the days were dreary and sunless. Then a strange, swift sickness fell on the island, and so many died, that from dawn to dark, and from dark to dawn, the wailing never ceased. It throbbed over the island from sea to sea, and mingled the cries of woe with the shrieking winds. "It is the strange mad woman of the mountains," said the high priest to the queen. "She calls, and the sick wind blows from the south; then the souls of the afflicted are lured into it, as the feather of a sea-bird is caught in the gale and carried no one knows whither. She is possessed of an evil spirit, and the wailing will not pass from the island of Hawaii until her body lies on the altar of the gods." That same day the queen sent messengers through the mountains, searching for the mad woman. They found her sitting on the rushes before her cabin, quietly weaving, and on her face rested the peace of the great silent forest She folded away her mats and went with them willingly, for her sufferings had drained her heart of fear. In the night the half-lulled storm rose again, and raged furiously. It tore the limbs from the trees and shrieked through the groves like the demons of Milu, and the surf rolled in endless thunder. From a hut in the temple courtyard a plaintive cry rose above the tempest: "Lei Makani! Lei Makani!" In the sleeping-house of the palace a young chief, who was called Olulo because he was found on the seashore, stirred uneasily on his mats. "Lei Makani! " came the call again, and he rose quickly and went out into the storm; but the rain on his face woke him, and he wondered why he had left his bed Then in the dark hut a sad, lonely chant rose and fell on the waves of the storm :

When the morning dawned one of the guard went to the queen and told her what he had heard, and the queen sent quickly to the temple in great fear that it might be too late ; but the high priest himself brought Haina Kolo to the palace. She is the wife of the chief of Waimanu who, these many years, has mourned for her," said the queen. "When he returned to Kauai after the long war they told him that, fearing he would never return, she had gone in search of him; and he himself found her wrecked canoe on the shore of the Island of Demons." "Auwei! Then she is the lost princess of Kauai!" "But the son, where is he?" The queen and the priest looked at each other in startled wonder. Send for old Niiu," said the priest. "He has but lately returned to these shores after many years." And the old fisherman, when he saw the woman sitting in the house of the queen, said, "It is the mother of the child I saw her searching among the rocks by the sea, but I had given the waif to the queen and could not take it back." The swiftest runner in all Hawaii, at the command of the queen, threw off his tapa and sped away over the rain-washed plains; and in the blast of the storm the chief of Waimanu returned, pace by pace, with the fleet-footed messenger. When father and son, the one gray with the years that had passed, and the other grown to a stalwart youth, stood before her, Haina Kolo knew them both; and the haunting shadows passed from her mind as the mist clears from the hills in the rays of the rising sun. And the forest where for so many years she lived in lonely solitude is still called The Forest of Haina Kolo. Back to Contents

RE you sure, Hina, that the earth has not grown since the days of my father?" The woman sitting on the rush-strewn ground looked up from her weaving of dried grasses, and a smile dawned slowly in her great, somber eyes. "The space between the stone and the sandalwood tree is the same, my son," she answered. "But the trees are larger. I remember when this one was only a single branch out of the ground; and you have often told me that when we came here to this forest, I was but a small child in your arms." "But the earth is past its youth, and the measure of its growth is backward." "Then tell me again," demanded the boy, throwing himself on the rushes beside his mother, "what manner of man was he who, standing on this stone, could throw a spear to yonder mark. Begin at the beginning, and tell me, how came he to the shores of this island?" Hina's thin brown fingers flew swiftly among the quivering strands, but the silence was unbroken for the space of a score of breaths, while the leaves whispered softly to a low-drifting cloud, and the sunshine glinted in the deep green tunnels of the forest. At last she spoke, and her voice, rich and low, filled and swelled the harmony of the bird-songs. "From out of the golden dawn floated his canoe," she said, "a tiny speck, shot by the rays of the rising sun across the shimmering blue. So swiftly it came the fishermen forgot the fish struggling in the nets, and stood chest-deep in the surf, waiting to see what being it was whose canoe cut he water like the fin of a spear-fish in chase. When the boat reached the rim of breakers on the reef it paused, then, obeying a mighty stroke of the paddle, leaped to the crest of a wave, and sped shoreward with the swiftness of an arrow sprung from a warrior's bow. "And I," interrupted the boy, "I have never seen a man save old Pakeo, who comes to our mountain to gather the brown floss of the treefern. But he is crooked and little, though he throws a swift spear. And then, mother Hina?" "And then, when they saw that the stranger bore the emblems of a high rank, they led him to the king, and the king received him as a noble guest. Very soon he became a member of the royal household, for he had great skill with the javelin and the long spear, and was wise in warfare." Hina paused, and the boy took up the tale eagerly. "And when the stranger had won the great joust before the king, he asked the high priest of the temple for his daughter. Mother, think you that the maids in the valley now are as beautiful as you are?" "As I, Hiku! The young girls are smooth skinned, with black, shining hair, and - "But the birds with the black feathers are not so beautiful as the little manu that is soft gray and white ; and the black cloud is the cloud of storm and fierce lightning. I like not the black things of the forest. Now, tell me of the time when my father brought us up here into the mountains, before the great battle on the plains." "It was after the fishermen had fled from the sea with the tale of the thousand war canoes ready to be launched from the shore of Lele, to descend on our coast. The king was calling in the chiefs and their warriors from the distant valleys of the island, and making ready a strong defense. Your father came, and taking you from my arms bade me follow him. High up in the mountains we climbed, into the depths of the forest Here, as you see it now, was the house ready for our use; mats were spread for the bed, and food was stored enough for many weeks. Giving you back to my arms, he stepped to yonder stone and threw his spear. Across the open it whistled, like the shrill call of a bird, and buried its point in the trunk of the sandalwood. When he brought back the spear, he said, 'My lance I leave to my son, and the mark on the tree for him to grow to. When he is strong and sure, and can plant the spear of his father in the heart of the scar, then, and not until then, must he leave the mountain and go down into the valley to learn the ways of men. Before he goes, give him the arrow that is fastened above the door, and if his hands are free of the stains of life-blood, it will show him the way and the task I leave him. I go to fight for his land and his king and to return no more. "Then calling to the gods to protect us, he went quickly away through the forest" "And he was killed?" whispered the boy, his eyes wide and wistful though he knew well the tale. "He was seen fighting beside the king till the last foe was down ; but his body was not among the dead, nor stood he among the living. Some said he was of the race of the gods, and they had called him." The sad voice ceased, but in the woman's dark eyes there burned a fire that seemed the driving force of the flying fingers; the weaving grasses trembled in the still air, and the warm, damp fragrance of the forest rose like incense to the noonday sun. On the rush-strewn ground Hiku lay thinking of the unknown hero whose son he was, until his waking fancies flowed unbroken into the marvels of dreamland adventure. The mother turned to speak again; but seeing him asleep, rose quietly and gathered her beautiful mats into a bundle. With another glance at the boy she slipped away through the trees, down the mountain on the further side, into the village of a people who knew her not, and traded the work of her busy hands for food. When the boy awoke, the shadow of the sandalwood lay twice the length of the stately trunk across the turf. He sprang to his feet, his eyes still alight with the fire of a dream-battle. "Hina! mother Hina!" he called softly. Only the woodland echo answered, and he stretched his lithe body, listening. In all the wide forest there was no human sound. The murmuring breeze, the rustle of growing things, the twitter of the birds but underscored the silence. Suddenly a laugh, clear and sweet though distant, floated up through the still air. Hiku bounded to the edge of a cliff overhanging the valley, and, throwing himself at full length on the rocks, peered eagerly over the brink.

His brows drew quickly together in an impatient frown, for, instead of a sunny green valley, he looked into a sea of fleecy vapor, through which the mountain tops rose to the clear, amber light of the waning day. Billows upon billows of tumbled whiteness covered the lowlands and sea, though the sound of laughing voices came up to the boy's ears, now clear, now muffled, as the clouds shifted in the freshening wind. So often Hiku had lain thus, listening and peering, but always the clouds or the thick underbrush baffled, and no one but old Pakeo had ever dared the mountain height, for the valley-folk believed it the abode of a sorceress. Hiku waited until the last sound died away; then he sprang to his feet and strode back to the hut, followed by the mocking cry of the birds. "'Twas a maid, 'twas a maid, 'twas a maid!" they seemed to call after him, and he crashed through the brush, his pulses throbbing riotously. Never before had he heard young voices so near, and the hot blood tingled through his veins to his finger-tips. It was the call of youth to youth, and all the lad's powerful strength responded. He swung across the clearing before the cabin, where Hina again sat at her weaving, and caught up the spear from the ground. For a moment he poised on the worn stone, his muscles slowly swelling and knotting under the brown, satiny skin. Then, swift as the dart of a scorpion's sting, his sinewy arm shot out, and recoiled, and the spear flew through the air, swift and true, into the very heart of the old scar. "Hina!" he shouted, "mother Hina! I have done it! See! See! The spear of my father again quivers in the trunk of the old tree!" The woman rose slowly to her feet, and stood uncertain dazed. Unexpectedly she reached the goal that, she had thought, was still many turns in the maze of the future. She watched Hiku spring to the tree and tear out the spear; then she turned and brought him the magic arrow. "It is yours," she said. "But the night comes swiftly. Wait now the new day, then go down into the valley. When you reach the foot of the mountain, shoot the arrow from your bow and follow its flight It will lead you; but fail not to return before the day is gone." In the early morning, as the sun came up out of the sea dripping showers of gold, Hiku left the cabin and ran eagerly down the mountainside, springing from ledge to ledge, leaping the rifts in the rocks, down through the thick mist of clouds into the long-dreamed-of valley. He drew his bow and shot the arrow out into the unknown world before him. It fell in an open field where young men were practicing with the javelin and the long spear. For a time he watched them curiously, then turned and fitted the arrow to his bow again. "These are but children," he thought, "I shall find men further on." At the second flight the arrow led him to a grove where men and women were drinking from a big bowl of awa. Some were reeling about singing, others were quarreling, while a few lay in heavy, noisy slumber; but it all looked foolish to the untaught boy, and he passed on. For the third time he drew the tense string of the bow, and followed the slender barb. It led him through taro patches and gardens, past village huts, into the courtyard of the high chief, where it dropped at the feet of a young girl. Laughingly she caught up the dart and hid it behind her as Hiku entered through the gateway. "How do I know it is yours?" she asked when he held out his hand ; and her lips made the youth think of the ripe, red ohias in the mountains. "My own will come to me," he answered, and whistled softly. Instantly the arrow slipped from her fingers and fluttered to his shoulder. "Auwei!" cried all the people in astonishment; and the old chief came out of his house at the sound "Who is this stranger?" he asked. "Hina, the daughter of Neula, is my mother," Hiku answered for himself, "and I bring my father's strong-bow to the service of the king." When Hiku entered into the new life, the old existence faded away to the dimness of a half-forgotten dream. The primeval forest, the hut in the clearing, even the lonely, waiting woman, were veiled from his memory, even as the dark peak was hidden from the valley by the thick curtain of mist that banked against the mountainside. Each day held new wonders: the bountiful feasts, the sports where his great strength won him high honor among the young men; the music, the dancing, the singing and laughter and jest; but more than all, the beautiful, laughing eyes of Kawelu, the fairest daughter of the chief, she at whose feet the arrow had fallen, held him enthralled. At last, in the darkness of the night, he awoke suddenly to find the magic arrow lying in his open hand With the touch came a quick, accusing thought of Hina, alone in the forest At once he arose and stole out of the sleeping village, and in the still dawn reached the hut. His mother sat on the rushes weaving, and he threw himself on his knees before her. "Give me your pardon, mother," he begged "I thought I was a man, but I have forgotten like a child" Hina stood up; taking his head between her hands she raised his face to the light and read in his eyes the honest shame of his heart "Ah, Hiku," you are but a lad after all, though a good lad, for you repent wholly." "Then come with me, mother Hina. Return to the village where you are still remembered and loved." Hina glanced about the little clearing where every tree, every stone was so familiar that she read the hour of the day in the shadows, and Hiku saw, growing in her face, the dread of change. With heart throbbing to return to the human life of the village, he set himself patiently to the task of stealing, one by one, the fears and misgivings from her mind. When she took up her work again he stretched his long limbs beside her, and began the tale of his adventures in the valley. To the boy, the days on the mountain dragged almost intolerably, but he waited resolutely for the woman's slower mind to wake to the desire for old associations. But though the peace of the mountain lay unbroken, the village in the valley seethed with excitement The powerful young chief who had won the favor of the whole clan had mysteriously disappeared; and Kawelu, his promised wife, lay on her couch of mats with her face to the wall. When, at last, Hiku persuaded his mother to return with him to the valley, they found the village a place of sorrow. Kawelu lay dead in thehouse of the chief, and the mourners wailed unceasingly. Hiku threw himself beside the couch inthe darkened room, and called upon the spirit ofhis beloved to return to him. No flutter of lifemoved the still heart; and sobbing he went outinto the fields. Fitting the magic arrow to hisbow, he cried: "Go, shaft of the gods, and search out the place where hides the spirit of Kawelu." Wide and long was the arc of its flight Hiku followed and saw it fall into a thicket where the rocks jut out into the sea at the foot of the great mountain. Beating the brush aside he found a cavern so deep and dark that eyes could not fathom its depth. Without returning to the village, he went away into the mountains. For three days he gathered vines, and wove them into a rope, long and strong, at the end of which he fastened a stout cross-bar of wood. He cut a cocoanut in halves, and taking out the meat, fitted the pieces together so that not even the smallest crack could be seen. Then, gaunt with sleeplessness, his eyes burning, he returned to the house of the chief. "Brothers of Kawelu," he said, "your sister is not dead. Weakened by grief her body held not strongly to the soul, and Milu, the evil one, snatched it away. Upon you I call for the strength of your stout arms to help rescue it from the deep caverns of the earth whither the fiend carried it "How know you that this is so?" asked one of the brothers. "My death be upon my own head/' he answered, "if I restore her not." At the mouth of the cave Hiku took his bow and arrow and the cocoanut shell, and stepping to the cross-bar of the swing, told the four brothers to lower him into the pit. Swinging dizzily like a spider at the end of a web, he slipped down, down, till the light gleamed like a star above him; down, down, deeper and deeper still in the fearful blackness. The air grew foul and dank, evil sounds hissed from the crevices of the rocky walls, and vile odors choked him. Away below a faint spark appeared a light that grew into a glow, then into a radiance; and he found himself in a vast cavern, the cavern of Milu, the evil god of the underworld. On the throne sat the demon, while about him were gathered the souls he had stolen; with them, her face hidden in her hands, crouched the spirit of Kawelu. As Hiku swung above her he called; she looked up, and then sprang to his arms. Milu shouted, and a tumult of echoes rolled under the vaulted roof; he commanded the spirit to leave her lover, and at once Hiku's arms were empty, but above his head hovered a beautiful white butterfly, which he caged in the cocoanut shell. When the fiend saw that Hiku held the spirit a prisoner, he caught up a lightning dart, but swifter still, the magic arrow sprang from the bow and buried itself in the heart of the monster. Through the son of Hina the gods had rid the world of a dreadful evil Hiku hastened back to the house of the chief, and when he opened the shell the rescued spirit entered again into the body of Kawelu, and she arose and greeted her lover and his mother as though she had but waked from a deep, restful sleep. Back to Contents