A

Cultural History of Three

Traditional Hawaiian Sites

on the

West Coast of Hawai'i Island

Overview of Hawaiian History

by Diane Lee Rhodes

(with some additions by Linda Wedel Greene)

|

Chapter 1: Before the Written Record Chapter 2: Early European Contact with the Hawaiian Islands Chapter 3: Foreign Population Grows Chapter 4: Founding of the Hawaiian Kingdom Chapter 5: Changes after the death of Kamehameha Chapter 6: Development and Human Activity on West Coast of the Island of Hawai`i Chapter 7: Pu'ukohola Heiau National Historic Site Chapter 8: Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park Chapter 9: Pu'uhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

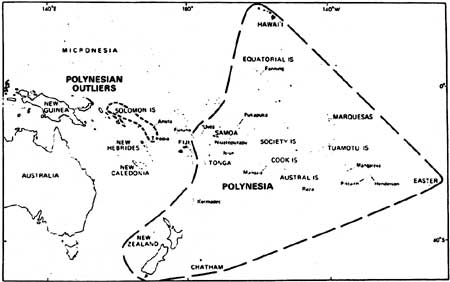

Chapter 1: Before the Written Record A. Formation and Description of the Hawaiian Archipelago Hawaii comprises the northern apex of the Polynesian Triangle (Illustration 1), the name given an area in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean stretching from New Zealand on the south to Hawai'i on the north to Easter Island on the east and encompassing several island groups. All of these populations are thought to be descended from a common ancestral society. The Hawaiian chain is among the most isolated areas in the world, lying approximately 2,100 nautical miles southwest of California and more than 4,000 miles from Japan and the Phillipines. As a consequence of their location, these islands were among the last areas in the world to be discovered and populated but also have served as an important link between North America and Asia. The greatest single distance between any two of the larger Hawaiian Islands is the eighty miles from Kaua'i to O'ahu, while the distances between adjacent islands average twenty-five miles or less. Except for certain wide and dangerous channels that limited communication in some directions, the earliest inhabitants were able to voyage among most islands of the group with relative ease by paddling or sailing canoes.

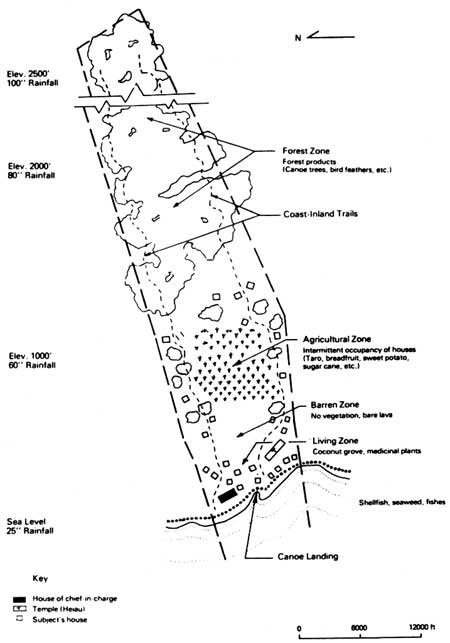

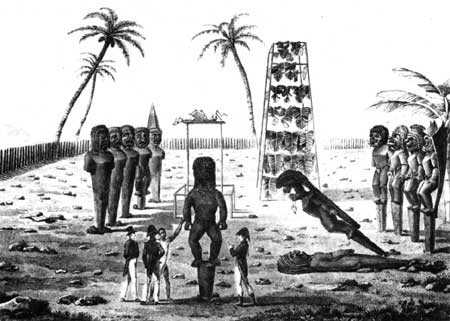

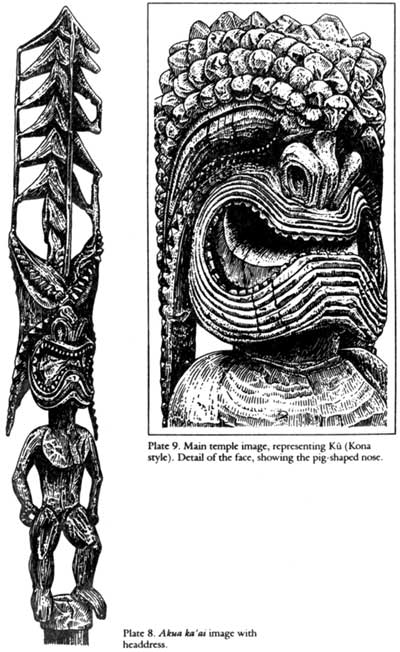

The entire Hawaiian archipelago consists of 132 islands, islets, sand cays, and reefs. Most of the total land area, however, is made up of five major islands — Hawai'i, Maui, O'ahu, Kaua'i, and Moloka'i — and three smaller ones — Lana'i, Ni'ihau, and Kahoolawe — stretching across the Tropic of Cancer. The island of Hawai'i, commonly known as the "Big Island," contains more than twice as much land as the other seven islands combined. The group lies between latitudes 19 degrees and 29 degrees North and longitudes 154 and 179 degrees West. The northern and central, most westerly, leeward islands are small, almost uninhabited, volcanic rocks and coral atolls. The two exceptions are Nihoa and Necker, which were uninhabited at the time of European discovery but contain archeological evidence of earlier human occupation. The larger islands of the Hawaiian chain comprise the emerged summits of a 1,600-mile-long northwest-southeast trending range of volcanic mountains resting on the Pacific Plate. These shield-shaped basaltic domes have been built up by successive outpourings of lava from vents along a crack in the earth's crust that cooled to solid rock bodies. These islands vary considerably in configuration, land area, rainfall, and vegetation. The oldest eruptive centers are at the northwest (Kaua'i, O'ahu) end of the chain, while the youngest, still active volcanoes are at the southeast end, including Kilauea and Mauna Loa (the world's largest active volcano) on Hawai'i Island. This youngest island has been the focal point of active vulcanism during the period of human occupation. Volcanic eruptions have been a frequent cause of population dislocation, burying settlements and agricultural land under sweeping lava flows. These flows preserve numerous important archeological sites. The different geological ages of the islands of the Hawaiian chain mean great differences in topography, bespeaking various stages of formation and erosion. The larger islands, which are all dome volcanoes, exhibit a gentle, gradual slope from summit to ocean. The central, mountainous parts of these islands are generally rugged and cover considerable area. Through the years volcanic flows have been subjected to various weathering processes. First chemical weathering gradually works upon the lava, resulting in formation of soil. That action is followed by rainfall-induced stream erosion associated with north-east trade winds — the dominant feature of the Hawaiian climate. Erosion is usually greater on the windward side of the islands where the greatest amounts of rain fall, causing the formation of steep valleys and cliffs, often cut by permanent streams. These predominantly wet, cool areas are forested where not cultivated. It has been estimated that almost fifty percent of the total area of the main islands (6,435 square miles) was forest land in pre-European times. The warmer and drier leeward sides of the islands, more sheltered from the rain, undergo much more gradual erosion and are mostly grassland and scrub, characterized by shallower, trough-like valleys, coastal plains, flat sand or cobble beaches, and occasional coral reefs. The mild, subtropical climate of Hawai'i has been favorable to the growth of introduced vegetation. Plants and animals native today are descendants of those that arrived over a long period of time by one means or another and spread gradually throughout the islands. Hawai'i's flora and fauna are highly specialized because of their isolation and the great variations in environment on the different islands. B. Origins of the Hawaiian Population Probably beginning about 1000 B.C. or earlier, small groups of people from western Melanesia or southeast Asia migrated toward the Pacific into the western part of Polynesia. Their colonization attempts were highly successful for several reasons. A seafaring population, they had developed strong double-hulled outrigger canoes that could carry many people and supplies and travel great distances. They had well developed celestial and other navigational skills that not only allowed far-flung colonization efforts but also enabled round trips between parent and daughter colonies. Finally, they had perfected the horticultural, hunting, and fishing technologies needed to sustain fledgling populations on previously uninhabited islands. These colonists, who became the ancestors of a hybrid people known today as Polynesians, ultimately spread to all other islands of the Triangle. The Hawaiians are a branch of these peoples inhabiting the eastern tier of islands in the Pacific Ocean. The other principal branches were the Maori of New Zealand and the Samoans, Tongans, Tahitians, Cook Islanders, and Marquesans. According to Anthropologist Patrick Kirch, there is strong evidence from a number of early Hawaiian archeological sites that initial colonization of some of the islands had occurred by at least the fourth or fifth centuries A.D. by people from the Marquesas Islands. It is thought there were additional waves of immigrants to Hawai'i beginning in the twelfth century from the Society Islands (Tahiti). Evidence exists, and Hawaiian tradition suggests, that the route between Tahiti and Hawai'i was traversed frequently by large double-hulled canoes during this later period, return voyages possibly being made to renew contacts and secure skilled labor and additional plants and animals. The role of external contacts (migrations) in the evolution of Hawaiian culture is still actively debated. Important new cultural elements forming the framework for the later Hawaiian labor system, social structure, and religious order were introduced during the final migratory period and superimposed upon the aboriginal society of earlier migrations. The leaders of these last arrivals were the ancestors of the ali'i, the chiefly class of Hawaiian society noted by the early discoverers, whose origin and cultural heritage were distinct from those of the older Hawaiian population. After this period of "long voyages" ended, communication ceased between Hawai'i and other areas of Polynesia, and the Hawaiians lived in nearly complete isolation from outside influences until 1778. C. Origins of Hawaiian Culture The early migrants from Central Polynesia did not arrive in Hawai'i totally unprepared for life in a new island setting. They brought with them a collective knowledge accumulated over thousands of years of migration from southeast Asia relative to subsistence activities, engineering techniques, adaptation to environmental constraints, and handicrafts that were suited to dealing with the raw materials of a tropical environment. The Polynesian culture of which these settlers were a part emphasized fishing and farming supplemented by dependence on domesticated animals. The development of this culture had also resulted in traditional ways of thinking and patterns of social behavior and formation of specific attitudes towards relationships among individuals and between individuals and nature. Peter H. Buck, a former director of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu, points out that there was no single Polynesian culture when foreigners first made contact. The only common culture would have existed when people were living in one island group before dispersing elsewhere. From that point on, each island group proceeded to develop its own culture, specializing in different directions while still retaining some fundamental elements of the early common culture. When the term "Polynesian culture" is applied to that functioning at the time of European contact, it is an abstraction referring to common features or general similarities underlying local differences in culture within Polynesia. The first voyagers to the Hawaiian Islands would have brought with them only some of the cultural variations and subsistence items present in the various Polynesian societies, which would have become the basic agricultural staples of the Hawaiian economy. Not only did these prehistoric peoples make extensive changes in the Hawaiian landscape, modifying and manipulating the habitat to suit their needs, but they also had to live with certain constraints exercised by nature that greatly affected the development of their culture. These factors set certain directions in terms of needed skills and a subsistence base and gradually led to a culture very distinct from the Polynesian homeland. The social and political organization and the religious practices that emerged as part of this new Hawaiian society were related to the peoples' past experiences as well as to their adaptations to the ecosystems of their new home. D. Development of Hawaiian Culture 1. Early Environment of the Hawaiian Islands The Hawaiian Islands consisted of high volcanic landforms separated by miles of open water. A great diversity of environmental conditions existed among islands and upon each one. The first Polynesians reaching this new homeland found a virtually unspoiled landscape. Although somewhat barren and dusty in places, there were as well undisturbed reefs and lagoons, sandy beaches, dense inland rain forests, broad alluvial plains, precipitous cliffs, high peaks, and moist valleys and uplands, in addition to a mild, salubrious climate. And until European contact the area remained relatively pest and disease free. The most serious deterrent to technological advancement was the absence of metals, such as copper and iron, in a usable form, forcing reliance on stone, wood, shell, and bone for tools, weapons, and household implements. Fortunately, one of the assets of their new home was an abundance of volcanic rocks, some of which were hard enough to be used as adzes, cutting implements, and abraders, while others could be broken up into blocks suitable for construction. Other types of stones, such as waterworn pebbles and talus fragments, were also used in building. The volcanic nature of their new home affected many aspects of the developing Hawaiian culture. The percentage of land available for cultivation was small. The rugged, mountainous interiors were neither conducive to habitation nor good for agriculture due to excessive rain and scarce sunlight. Some areas of the islands had abundant water, while others were very dry. Tidal waves, mud and rock slides, and volcanic eruptions were a constant threat, undoubtedly causing considerable damage and loss of life. Seasonal flooding, droughts, and other environmental conditions seriously affected agricultural as well as maritime pursuits and necessitated careful planning and community cooperation to insure an adequate and constant food supply. All things considered, however, these pristine tropical islands offered an abundance of raw materials and a favorable environment for the formation of a distinctive socially and politically complex culture. The archeological profession is still actively debating the nature of pre-Western contact Hawaiian culture. This has resulted in the formation of several models illustrating the evolution of Hawaiian settlement and subsistence patterns, material culture, and socio-political organization. A detailed analysis of each of these models is not presented here, but rather a summary of the probable general development pattern of Hawaiian society prior to the arrival of Europeans. 2. Settlement Patterns and House Styles Over the last twenty years archeologists have begun intensive investigations into the nature and patterns of aboriginal cultural adaptations to the varied environmental situations found in the Hawaiian Islands. The term "settlement patterns" refers to the nature and distribution of dwellings and other buildings reflecting the natural environment, level of technology, class differences, trade patterns, warfare, political and religious systems, and cultural traditions. Little is known about the earliest Hawaiian population, but because of their Polynesian background as fishermen and agriculturalists, during this formative time settlement probably began along the coastlines near rich fishing grounds. These scattered, often temporary, coastal homesteads, consisting of a few houses, were probably occupied by extended family groups. Although the character of a shoreline might seem promising for a village site, its selection depended upon shelter from winds and the availability of fresh water. In ancient times, water was available from several different sources. Surface streams in the larger valleys provided water for domestic use and later were used for irrigation purposes. Along the coastal plains, ground water was available in volcanic rock, limestone, and gravel. This lower-level fresh water (basal water) floats on the salt water because of its lesser specific gravity. Where there were no streams, coastal villages depended on basal water obtained from shallow wells dug in the sand a few feet from the shore. In some areas fresh water escaped along the coasts, causing springs under the surface to erupt through the salt water. This water could be captured in gourds for use. Settlement also extended into the lowland zone of alluvial windward valleys where there were fertile agricultural resources. Initially, some of the settlers living farther away from the coast on the hillsides and in the valleys where there were many rock caves, might have used these for housing. At some point these first arrivals began constructing shelters and arched dwellings of wood and bark on level spots along the curves of the land, along sandy shores and the banks of streams, on ridges and hills, and in gulches and wooded areas — wherever suitable material for thatching existed. Some evidence has been found that these early settlement structures contained fire hearths and that cooking was done in traditional Polynesian earth ovens. In time, the focus of permanent settlement became the fertile, well-watered windward valleys, but with continued exploitation of rich fishing grounds. Activities were not confined to the windward lowlands, and eventually small permanent nucleated settlements became dispersed throughout ecologically favorable locations on all the major islands. The archipelago's population was probably increasing, due in large part to the lack of restrictions on agricultural land and to plentiful natural resources. Evidence of house structures from this period reveals small, round-ended huts with internal, stone-lined hearths. Other types of houses, including rectangular shelters, might also have been present. Explosive population growth ultimately necessitated expansion into even the most arid and marginal regions of the archipelago. During that time, the population established numerous new sites and settlements, mostly in previously unoccupied areas. Small clusters of houses continued to appear in the interior portions of windward valleys, away from the coast, and along leeward coastlines. The first settlements in these latter areas were situated at the most favorable spots, near natural fishponds or around sheltered inlets. This period was characterized by the rapid dispersal of population from the fertile windward regions into leeward valleys and along leeward coasts. Throughout this period the continued settlement and development of less favorable areas occurred. Large numbers of rockshelters now served for both temporary and permanent occupation. Houses with rounded ends persisted in limited numbers, but the dominant permanent house style was rectangular. These structures frequently rested on stone-faced, earth-filled rectangular terraces, and a pattern of separate dwellings and cookhouses was established. The C-shaped shelter also appeared during this time, correlating with the development of leeward agricultural field systems. Just prior to contact, there were few significant lowland tracts not subject to some level of occupation and exploitation. An apparent decline in growth rates, however, led at this time to a leveling off of the population. The effect of such controls as abortion, infanticide, and warfare on this trend is uncertain. 3. Material Culture Little is known about the earliest Hawaiian material culture. Stone adzes of various types were certainly used, and because these people were fishermen, depending initially almost entirely upon the sea and its produce for their subsistence, simple fishhooks were manufactured as well as trolling lures. Other items found from this early period include coral abraders and flake tools. Cultural items most susceptible to change during the settlement period would have been those used in sea exploitation, because of the different raw materials, marine conditions, and types of marine resources in Hawai'i. Ultimately certain distinctive patterns of Hawaiian material culture did begin to develop. Fishing gear was refined to adjust to local marine environmental conditions and available materials. Elaborate two-piece bone fishhooks appeared and trolling lures became more distinctive. Styles of coral and sea-urchin files, awls, scrapers, and flake tools remained about the same. Few new portable artifact types developed over the years, and the basic Hawaiian material culture inventory changed little until the arrival of Europeans and the introduction of foreign goods and materials. However, elaboration of elite status goods, such as feather capes and whale ivory pendants, and wood carving increased. Craft specialists standardized and controlled the production of these valued goods as well as of utilitarian items. At the time of European contact, these status items were much admired for their design and artistry. 4. Subsistence If the Hawaiian settlers had been totally dependent on the land resources of the islands they were settling, it would have been very difficult to survive. The upland forests, often extending to the foothills, provided some food plants such as pandanus and edible ferns. The forests also were habitat for bats and birds, which could be utilized for food, while the feathers of the latter also became an important aspect of personal ornamentation. In addition, the fertile soil and water resources could be exploited for agricultural purposes. These indigenous island resources were supplemented by a limited number of plants and animals the voyagers brought with them by canoe. These included taro, yams, and breadfruit (not successfully transplanted until the 1200s); fiber plants like the paper mulberry whose bark could be manufactured into clothing and decorative items; medicinal plants of many varieties; and a few domesticated pigs, dogs, and fowl. However, careful tending of these food plants and domesticated animals for several years would have been necessary before they could provide an adequate food supply. The early settlement period, therefore, was probably characterized by primary dependence on the sea and its products for subsistence. On adjacent land, however, if sufficient rainfall and protection from salt spray allowed, the villagers could raise sweet potatoes or yams. Expert fishermen, the first settlers were adept at exploiting the rich marine resources found in nearby reefs and bays, including fish, shellfish, squid, crustaceans, marine mammals, and seaweed. They not only rapidly became familiar with the various habits and characteristics of the different kinds of fish on the coasts and the best places and times to catch them, but also acquired an intimate knowledge of their breeding places and feeding grounds. This almost total dependence on the sea would last until crops were growing well and domesticated animals were reproducing in sufficient numbers, allowing the Hawaiians to expand into a land-oriented economy. In time there was extensive development and intensification of all aspects of food production. Fishing and shellfish-gathering continued as a major specialized activity. The Hawaiians not only became adept at spearing and poisoning fish, but also at formulating precise techniques for the manufacture of fishhooks, lures, basket traps, and nets with sinkers. The population also collected salt for treating pork and fish in dry coastal areas by evaporation, frequently in natural or manmade saltpans. Economic production intensified with the development of large irrigation works, dryland field systems, and methods of aquacultural production. There is direct archeological evidence for taro Irrigation in the form of stone-faced pondfields and irrigation channels constructed in interior valleys. These irrigation systems reflect the intensification of production in areas that had already been occupied for centuries. Leeward areas, however, also underwent rapid agricultural expansion as dryland forests and scrub were cleared and various kinds of field systems were laid out. The first true fishponds and associated aquacultural techniques probably developed during the latter half of this period. The earliest ponds were constructed by the fifteenth century and Increasingly thereafter as chiefs could command the labor necessary to transport the tons of rock and coral used in the enclosing walls. These ponds, which yielded several hundred pounds of fish per acre annually, were not only feats of engineering technology, but reflected chiefly power and were a major symbol of the intensification of agricultural and aquacultural production. Many of the larger pondfield irrigation systems in the valley bottoms appeared in the final centuries prior to European contact. In addition, a large number of fishponds were constructed along the island coasts, under the direct control of the chiefly class. During the early colonization period in the islands, Hawaiian society probably remained structured along the lines of its ancestral concept of hereditary chieftainship, with settlers organized into corporate descent groups. The rank differential between chiefs and commoners was probably not great for the first few centuries after settlement when bonds of kinship would still have been important in a small population group. The precise nature of the religious beliefs of this early population is unknown, although the pan-Polynesian concepts of mana (spiritual or supernatural power) and kapu (taboo) were probably still a part of their social and ritual lives. Sacred places were probably only designated by small platforms or some type of enclosure. Eventually a distinctive Hawaiian cultural pattern began to emerge. Although little is known about this stage of socio-political and religious systems, the discovery of some elaborate burials from this period indicates that some sort of status differentiation between chiefs and commoners existed. Probably the ancestral pattern of corporate descent groups had not yet given way to the later rigid class stratification. In time, the socio-political structure of Hawai'i underwent a radical change, resulting in new forms of religious belief and ritual, in increasing rank differences, and in formation and stabilization of the basic social and political framework found at European contact. The increase in population was a major factor underlying these substantive changes. The spread of settlement into previously unoccupied lands, the establishment of inland field systems, and the dispersed residential pattern provided significant opportunities for agricultural development and intensification, for territorial and political reorganization, and for intergroup competition. Ultimately, corporate descent groups no longer held land in common. That system was replaced by the ahupua'a pattern characterized by territorial units under the control of subchiefs owing allegiance to a central chief and subject to redistribution in the event of conquest and annexation by a new ruling chief. The establishment of the ahupua'a as the central unit of territorial organization probably dates from this time. As the amount of land available for agriculture diminished, the definition of territorial boundaries increased and local conflicts over arable land brought about intergroup warfare and competition among chiefs. Success in warfare enabled increasingly powerful chiefs to annex conquered lands and place the control of ahupua'a units in the hands of their lesser chiefs. Ultimately, rigid class stratification and territorial rather than kin- based social groupings were established. Because it was so closely interrelated with these social and political changes, the religious system underwent significant development and elaboration. The Makahiki ceremony, closely tied to the ahupua'a pattern of territorial organization, probably began at this time, developing by the end of this period into a ritualized system of tribute exaction. The rise of intergroup warfare and conflict probably arose with the elaboration of the Ku cult, which was accompanied by an emphasis on increasingly massive temples (heiau). By the end of this period, Hawaiian culture had been substantially transformed from its ancestral Polynesian predecessor; the basic technological, social, political, and religious patterns witnessed at European contact were now in place. In 1810 Kamehameha completed the unification of the Hawaiian Islands, basically ending the old political order. This was also the approximate time that foreign goods and ideas began to make serious inroads on the native culture. A wealth of oral traditions handed down by such nineteenth-century scholars as Samuel Kamakau, John Papa I'i, David Malo, and Abraham Fornander provide much information on the political developments of Hawaiian society at this time. (Kmakau, Papa I'i, and Malo were native historians. Fornander is an important source whose writings should be carefully evaluated due to religious influences and some questionable interpretations.) The political history of all the major islands during the final two centuries prior to European contact comprised constant attempts by ruling chiefs to extend their domains through conquest and annexation of lands, with campaigns often extending beyond the borders of individual islands. The expansion of a chiefdom was generally short-lived due to usurpation by a junior chief enlisting the aid of various malcontents. The later political history of the islands was therefore very cyclical. Another significant aspect of this late-period political organization was the system of marriage alliances between ruling lines of various islands. During this period, high-ranking women were regarded as the main transmitters of rank and mana. Various cultural elaborations resulted from the intense rivalry and warfare and cyclical conquest characteristic of highly advanced chiefdoms as they attempt to unify and emerge as states. The Ku cult rose in importance, resulting in construction of increasingly massive luakini (temples of human sacrifice). The kapu system, especially the sanctions surrounding the high chiefs, also underwent further elaboration. E. Major Aspects of Traditional Hawaiian Culture The previous sections have provided the reader with an overview of the origins of the colonizers of the Hawaiian Islands, the type of environment the original inhabitants encountered, and some idea of the major trends in the development of Hawaiian society during specific cultural sequences. Pu'ukohola Heiau National Historic Site and Kaloko-Honokohau and Pu'uhonua o Honaunau National Historical Parks contain a vast number of resources representing the evolution of Hawaiian settlement patterns and house types; fishing and agricultural activities; social, political, religious, economic, and land use systems; and recreational and artistic pursuits. These resources include habitation, recreational, and religious sites; items of material culture, such as tools, utensils, and artwork; roads and trails; and structures associated with agriculture, husbandry, and fishing, including shrines, windbreaks, fences, and animal pens. In order to better understand the contexts within which these remains attain their significance, it is necessary to describe in more detail some of the developments in Hawaiian culture up to the time of European contact. 1. Social Organization a) Stratification During the period from about A.D. 1400 to European contact, Hawaiian society underwent a systematic transformation from its ancestral Polynesian descent-group system to a state-like society. The stratification that came to characterize Hawaiian society — consisting of a highly cultivated upper class with territorial control supported by a substructure of an underprivileged lower class — was somewhat reminiscent of ancient Mediterranean and Asian civilizations as well as of medieval Europe, and indeed has been referred to as feudal in nature. The ali'i attained high social rank in several ways: by heredity, by appointment to political office, by marriage, or by right of conquest. The first was determined at birth, the others by the outcomes of war and political intrigue. At the time of European contact in 1778, Hawaiian society comprised four levels: the ali'i, the ruling class of chiefs and nobles (kings, high chiefs, low chiefs) considered to be of divine origin; the kahuna, the priests and master craftsmen (experts in medicine, religion, technology, natural resource management, and similar areas), who ranked near the top of the social scale; the maka'ainana, those who lived on the land, the commoners — primarily laborers, cultivators, fishermen, house and canoe builders, bird catchers who collected feathers for capes, cloaks, and helmets, and the like; and the kauwa, social outcasts! "untouchables" — possibly lawbreakers or war captives, who were considered "unclean" or kapu, that is, ritually polluting to aristocrats. Their position was hereditary, and they were attached to "masters" in some sort of servitude status. b) Rights and Duties of Each Class Earlier it was stated that the ali'i are thought to have arrived in the Hawaiian Islands after initial colonization had occurred. According to E.S. Craighill Handy, the origin and cultural heritage of the ali'i, who had earlier invaded and conquered aboriginal populations in central Polynesia, distinguished them from the older Hawaiian population. Historically and socially different, they maintained the purity of their blood and the integrity of their cultural heritage through barriers of kapu that isolated them from the lower echelons. Varying degrees of sanctity existed among the ali'i, the highest kapu belonging to an ali'i born to an ali'i of supreme rank and his full sister. In his/her presence, commoners prostrated themselves. The Hawaiian Islands are the only place in Polynesia where this type of extreme inbreeding was sanctioned, although only among the chiefly class, and the only place where the prostration kapu (kapu moe) was imposed. Recognized degrees of superior sacredness demanded special deference. All nobles of lesser rank had to observe prescribed forms of obeisance to those of the several sacred ranks and avoid their persons and personal property. Death resulted from failure to observe the proper form of homage. Lesser nobles occupied degrees of rank that were significant in connection with marriage and offspring but not in relation to the entire community. The mass of the people, the maka'ainana, probably descended from the aboriginal Hawaiian population. They performed many duties for their social superiors, producing food, supplying items for clothing and home furnishings, and laboring on community projects such as roads, water courses, taro patches, fortifications, and temples. A division existed not only between classes but also between the duties of commoner men and women. While men engaged in farming, deep sea fishing, manufacturing tools and weapons, building houses, and conducting religious rituals, women raised the children, helped in some agricultural tasks and in-shore fishing, collected wild foods, and made barkcloth, mats, and baskets. c) Role of the Kapu System The Hawaiian concept of the universe embodied the interrelationship of the gods, man, and nature. The former, although the ultimate controlling influence in this system, granted their direct descendants — the nobility — secular control over the land, the sea, and their resources:

Power and prestige, and thus class divisions, were defined in terms of mana. Although the gods were the full embodiment of this sacredness, the nobility possessed it to a high degree because of their close genealogical ties to those deities. The priests ratified this relationship by conducting ceremonies of propitiation and dedication on behalf of the chiefs, which also provided ideological security for the commoners who believed the gods were the power behind natural forces. Commoners possessed little mana and were therefore prohibited from entering any of the holy places where nobles and gods communicated, such as the heiau in which the aristocrats honored their gods. Pariah, with no mana, could interact with commoners but not approach aristocrats. Mana was the central concept underlying the elaborate kapu system of Hawai'i, the major social control perpetuating rigid class distinctions and conserving natural resources. As Handy states:

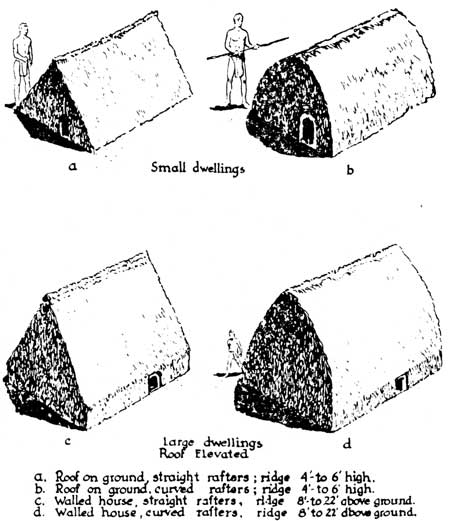

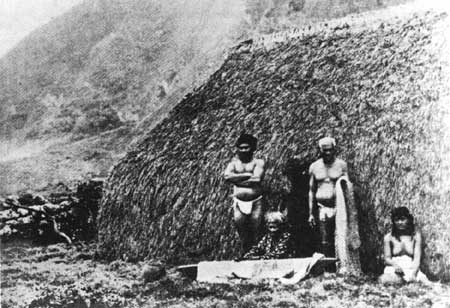

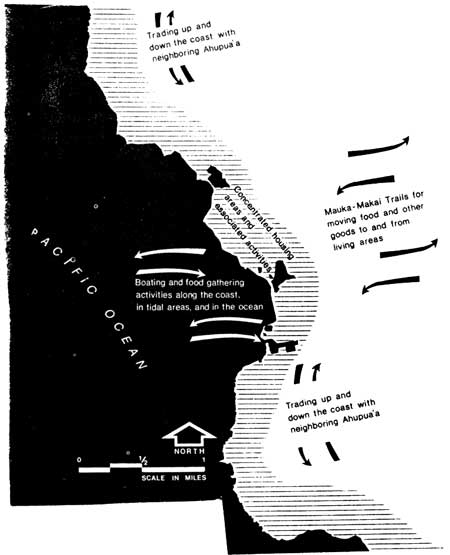

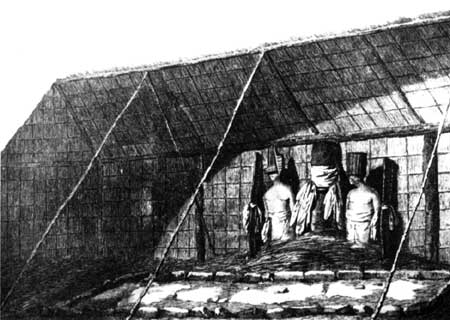

2. Settlement Patterns a) Location of Houses Ancient Hawai'i contained no large villages because of the need to reserve as much land as possible for cultivation or as fishing sites and because concentration of the population for governmental and business purposes was not integral to the functioning of society. The terms "village'' and ''town" as used in this report regarding early Hawaiian settlements do not denote a corporate social entity as they do today, but a forced proximity of homes to each other because of the topography or physical character of an area or the concentration of a particular activity, such as fishing, at that location. Most permanent villages initially were near the sea and sheltered beaches, which provided access to good fishing grounds as well as facilitating canoe travel between settlements. The majority of the population maintained these permanent residences along the coast and erected temporary shelters inland for use while exploiting forest products and working in taro and sweet potato fields. Both windward and leeward coasts of the Hawaiian Islands had their virtues and defects. As habitation sites, windward coasts were well watered but susceptible to choppy seas, a lack of sunshine, and often harbored steep cliffs. Leeward coasts offered safer navigation, were sunny and warm, but sometimes lacked water for agricultural and domestic use. Leeward coasts possessed of abundant water were considered ideal habitation sites. According to Archeologist Ross Cordy, recent study indicates that the first population centers on the larger Hawaiian islands existed on the windward sides, probably primarily in fertile valleys but extending into areas with good fishing. Permanent occupation of leeward areas did not begin until later. By about A.D. 1400 population had begun expanding inland from the coast, increasing throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries as scattered homes and small settlements were established near extensive permanent inland irrigation fields and in specialized agricultural areas. The district chief resided mostly among the largest centers of population, near the most productive resource areas, where there was enough food to feed his immediate family and relatives. His retainers, including lesser chiefs, warriors, and priests, settled nearby, creating a village atmosphere. Tenants of the ahupua'a provided food and goods to the court. District chiefs tended to move about, concentrating on good surfing or fishing areas, and distributing the burden of their support among the people. This constant movement also enabled them to keep a critical eye on their subjects and ferret out any unrest. b) Construction Techniques Houses of many different construction types existed in the Hawaiian Islands. Usually a commoner constructed his house with the help of friends. When a chief needed a house, however, his retainers assembled the materials and erected the structure under the direction of an individual (kahuna) expert in the art of erecting a framework and applying thatch. Every step of the house building process, from the selection of the site to the final dedication, required careful religious supervision. Certain prescribed rules governed not only the house's location, but also the method of construction, the arrangement of the mats for sleeping, and the procedure for moving in. Blessings such as long life were expected to result from proper respect of these rules. Most houses at the time of Cook's discovery of the Hawaiian Islands consisted of a framework of posts, poles, and slender rods — often set on a paving or low platform foundation — lashed together with a coarse twine made of beaten and twisted bark, vines, or grassy fibers and covered with ti, pandanus, or sugarcane leaves, or a thatch of pili grass or other appropriate material. When covered with small bundles of grass laid side by side in overlapping tiers, these structures were described as resembling haystacks (Illustrations 2 and 3). One door and frequently an additional small "air hole" provided ventilation and light, while air also passed through the thatching. Grass or palm leaves covered the raised earth floors of these houses.

c) Size of Residences Residences of the Hawaiian people varied in size because of differences in use based on class and social status. A commoner's family probably occupied only one or two structures — a sleeping house and perhaps a cooking or utility house, with an associated work plaza for kapa making and other outdoor activities (Illustration 4) Households by the sea kept their canoes in sheds and farmers might have storehouses. Furnishings in the homes of commoners were almost nonexistent, consisting only of some mats used as floor coverings and, when covered with kapa, as beds; a variety of containers; poi boards and calabashes; some simple tools; fish lines and nets; and weapons of war. Commoner's houses were primarily used only for storage and shelter in inclement weather; most daily household activities, such as cooking, took place outside. These houses also served as places of security or hiding places for commoners and lesser chiefs during kapu periods while high chiefs and high priests conducted important religious activities, such as burials or temple ceremonies, that needed to be free from prying eyes.

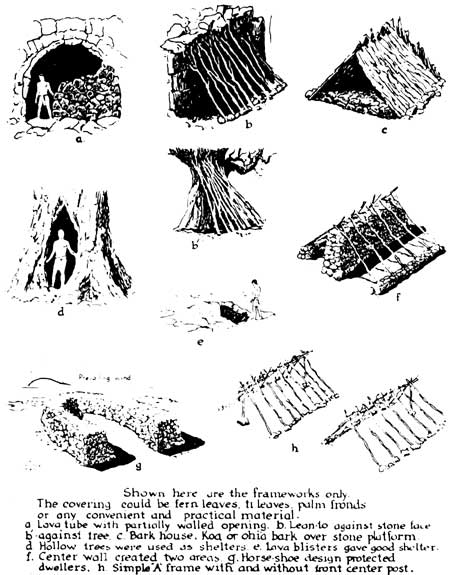

The families of chiefs occupied their structures day and night, good weather or bad. The household of a Hawaiian of rank or position, therefore, would need six or more houses. This is because separate structures had to be built for different purposes, the kapu forbidding eating and sleeping under the same roof and prohibiting men and women from eating or working together. The typical household cluster of a chief or other person of rank or position would include one or more of the following: a common sleeping house, a men's house for eating and cooking that was kapu to women, a women's eating house, a women's work house for making mats and beating kapa, a private retreat house for women during their menstrual period, and a heiau or house temple for worship of the family gods. At least one house of each chief's complex served as an office, conference room, and reception area for important visitors. Chiefs tended to stay inside most of the time, shielding their person and their mana from the view of commoners. A high chief possessed at least one complex of permanent thatched houses surrounded by a fence, while a ruling chief and other high-ranking individuals maintained several such complexes in different locations or districts. A ruling chief moved his court as desired, travelling along the coasts by canoe with his retinue and setting up temporary establishments at certain sites for purposes of business or pleasure. Numerous individuals, possibly as many as 100 people including family members, relatives, friends, and servants, attended and supported each chief. These retainers, each with specific duties such as preparing food or carrying the chief's spittoon, lived near the chief and moved when he did. Most of the families in this complex organization lived outside the chief's enclosure, but also required thatched houses for storage, shelter, and security during kapu periods. Probably the higher a chief's rank, the larger his stockade and more numerous his houses. d) Shelters Shelters at worksites for farmers, canoe makers, bark scrapers, salt makers, fishermen, and quarrymen; at short-term special-use camps for those working at a distance from their permanent home or involved in resource procurement; or at rest stops along trails when traveling were a necessity (Illustration 5). These temporary abodes took a variety of forms, including caves, stone wall windbreaks, lava tubes, lean-tos, hollow trees, simple A-frame structures, or bark houses. Shelters in the non-irrigated inland agricultural areas and in the forests where people were raising crops, hunting birds, gathering vines, or cutting timber, protected against heat, cold, wind, and rain. Shelters on the coasts, and especially on barren lava flows, provided relief from the sun or inclement weather or were used as windbreaks when sleeping. Chiefs and their retinues lived in temporary shelters when travelling by canoe along the coasts to establish temporary settlements for business or recreational pursuits. Apparently some commoners, regarded somewhat as vagrants by the rest of the population, used caves, lava tubes, or lean-tos as permanent abodes. Sheds thatched only on the roof were erected near the shore to provide shelter for canoes during construction and storage periods and shade for craftsmen working on them.

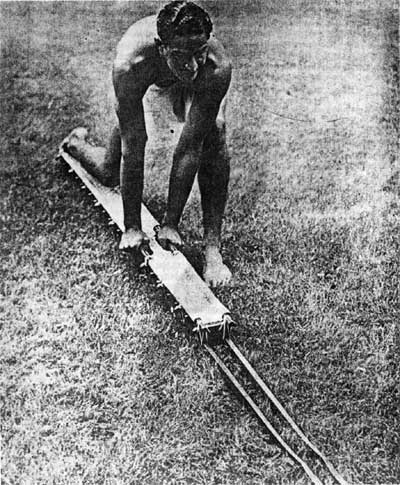

3. Subsistence a) Marine Activities (1) Inshore and Offshore Fishing (a) Techniques Abundant marine resources, including aquatic plants such as seaweed and edible algae and animals such as crustaceans and shellfish, provided the primary protein component of the Hawaiian diet because of the limited supply of other protein foods such as pig, dog, chicken, and wild birds. The ancient Hawaiians quickly became familiar with the various species of fish frequenting the waters adjacent to their shores, closely studying their habits and feeding grounds and adopting gathering methods suited to their particular characteristics. Although a constant, Fishing took place both inshore and offshore. Many fishing techniques were used, each demanding different equipment and procedures. The principal open sea marine exploitation practices at the time of European contact included hand catching, snaring, spearing, basket trapping, netting, hook and line fishing, and poisoning. Inshore fishing was probably the most productive and reliable source of seafood for the ancient Hawaiians, yielding fish, echinoderms, crustaceans, molluscs, and edible seaweed. Women and children participated in this type of fishing, although canoe fishing and even several of the reef methods were restricted to men. Several types of fish, including crabs, lobsters, eels, sea urchins, shellfish, octopi, and shrimp, could be caught by hand along the rocky coasts in shallow coral reef areas and shoreline pools or by divers in underwater caves. Eels and lobsters could be caught by snaring with a noose hung from a pole. When an eel stuck its head outside its hole to get at the bait on the other side of the noose, the noose was drawn tight and the eel ensnared and raised to the surface. Using hardwood spears about six feet long, underwater divers stood on the bottom of the shore and impaled fish as they swam by. Spears were used above water for turtles, octopi, and fish that were mesmerized by torches at night in shallow water. Women used basket traps to catch shrimp and fish. Woven of vines or branches and filled with bait, these baskets could be lowered to the shallow bottom. Women then dove down and brought the filled traps to the surface. More sophisticated baskets had conical woven entries, making it impossible for the fish to find their way out. Several types of gill nets were used, according to the type of fish to be caught and the type of habitat. The three techniques of fishing with these involved setting up a stationary net in which fish became entangled as they swam about; driving the fish into a stationary net; or moving the net to encircle the fish. Seine nets were also used in shallow water and trapped fish by impounding them within a complete circle formed by the net or between the net and the shoreline. Bag nets were made into enclosed purses with one open end in which bait attracted fish. A leguminous plant called 'auhuhu was pounded to make a material called hola; this was applied to holes or tidal pools to stupefy the fish, which floated to the surface where they could be retrieved in scoop nets. Or divers stuffed the pounded fibers into an underwater cave that had been sealed earlier to trap the fish inside. In a few minutes the dead fish were retrieved by hand. Another plant, called akia, found in the forests and foothills also served this purpose. Professionals did most of the offshore fishing, using canoes to reach the deep sea fishing grounds. Only through long and careful training did men become acknowledged fishermen. The head fisherman of a group, for whom this activity was a profession and sole occupation, was the po'o lawai'a. He could be a chief of lower rank or a commoner and often supervised a company of apprentices. Knowledge of the habitats and movements of different species of fish, of the methods of capturing them, and of the types of fishing apparatus needed and of how to manufacture them (these were usually made for him by craftsmen) had been handed down to him. It was therefore his duty to choose pupils to whom to transmit his expertise so the cycle could continue. His assistants helped in fishing beyond the reef, an activity that needed to be done in concert. Often one member of the party stayed on shore to watch for the schools of fish, whose location he signalled to the fishermen. The po'o lawai'a could be commanded to accompany the high chief for a sporting fishing expedition, he could be ordered to fish for the chief, or he could go whenever he wanted. Knowledge of the location of good fishing places off shore was a family or community possession. These spots were defined by taking bearings on natural features on shore. Several kinds of line fishing from canoes were practiced. The primary type was trolling for tunas with an unbarbed trolling hook, or lure. At other times a one-piece bone or shell hook was attached to a line, sometimes 600 feet long, weighted at the bottom with a stone sinker. Hooks were fastened to the ends of short sticks standing out at right angles along its length, which caught different kinds of fish frequenting different depths. The first fish caught were reserved for the gods and offered on altars on shore or given to priests as soon as the canoes landed. The best fish of the catch were then set aside for the chief's personal needs and those of his household. After apportions had been made to the various kahuna and konohiki (resident land manager of the high chief), the common people finally received their share according to their need. Resources caught along the coasts and on reefs were usually eaten raw. Fish were caught mainly for immediate consumption, but surpluses could be preserved by drying or by salting and drying on racks in the sun along the beach. Salt fish went especially well with poi, the staple Hawaiian plant food. Preserved fish could be stored for later food needs or became an important article in internal and external trade or exchange. Fish could also be wrapped in ti leaves and cooked in an imu (underground oven), laid on coals and cooked, or boiled in a calabash (gourd bowl). As mentioned earlier, salt was an important adjunct to the fishing industry, with villagers collecting and evaporating sea water in either naturally or artificially pan-shaped rocks along the shore. The extraction of salt from ocean water for domestic use was an ancient art. (b) Religious Aspects As with so many other activities in early Hawaiian life, success in fishing was closely tied to signs, omens, and the will of the gods. At the beginning of the fishing season, many ceremonies took place in which offerings such as pigs, coconuts, and bananas were made. There were also specific ceremonies surrounding the christening of a new canoe, the initial use of a new net or hook, and the catching of the first fish. Many deities were associated with fishing. Although an ancient noted fisherman Ku'ula-kai, his wife Hina-hele, and their son Aiai, were the chief deities of this activity because they supposedly presided over the sea, each fisherman also had his own god, which might be a stone or image of the family guardian spirit ('aumakua), which would bring good luck in fishing and to which he said prayers and made offerings. 'Aumakua belonged to and protected families, or a group of kinsmen, and passed from generation to generation. They were thought to be ancestors of these kinship groups. Good-luck stones, sometimes carved with human form or in the shape of a fish, were either taken along when fishing or left at home facing the sea. In addition, a variety of shrines and altars were placed along the shore near villages or fishing places. Fishing shrines (ko'a), comprising a pile of stones usually of coral or limestone, were erected on promontories or headlands overlooking the ocean. Ko'a also took the form of small thatched temples built on rock platforms, which were enclosed with wooden fences or rock walls and sheltered by banana trees. All these structures were designed to entice the deities to attract shoals of fish to the area, and offerings of fish and sometimes fishhooks were placed on them prior to setting out to sea. After successful fishing expeditions, fishermen again placed offerings of fish on their altars. Missionary William Ellis, describing his tour around Hawai'i in 1823, mentions that upon

As mentioned, the protective spirit of an 'aumakua was considered to be related to a specific kinship group. This was because the Hawaiians thought that the spirit of an illustrious deceased relative or young child could be ritually induced to enter some kind of fetish, either an inanimate object, a carved image, or an animal, and thus become a patron. The animal selected as the receptacle of the spirit would be treated as a pet, and a familiar relationship between its species and the family would be established. The early Hawaiians regarded certain sea animals, such as sea turtles, eels, squids, porpoises, and most notably sharks, as the physical embodiments of personal gods ('aumakua). Ellis conjectured that

If a species of shark were 'aumakua, any of its members received offerings for special favors, such as good luck at sea and protection from drowning, prior to embarkation of a fishing expedition. Many fishermen, however, regularly fed a shark at a special spot along the shore or from a canoe and came to recognize them as individuals and even as pets. According to J. S. Emerson,

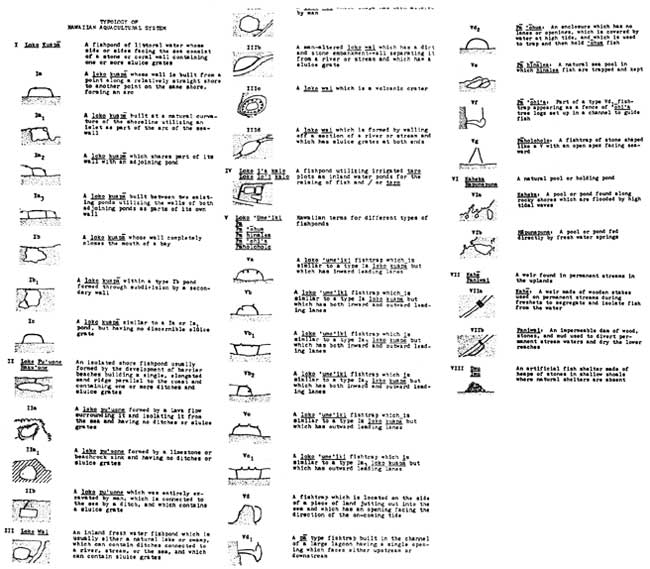

Religious practices related to fishing not only helped ensure successful fishing ventures, but the kapu related to fishing and fishponds also helped conserve the sea's food supply. These kapu were rigidly adhered to, not only through tradition, but because it was the will of the chiefs and of the gods and one could expect severe punishment for ignoring them. Hawaiian exploitation patterns were designed to preserve fishing grounds by tapping specific types of marine biota at certain periods. Kapu, or closed, seasons on certain fish during their spawning time helped in the conservation of that species. Elaborate religious ceremonies accompanied the switches in open fishing seasons. Other kapu involved prohibiting fishing at certain places along the shore when deep sea fishing was open; alternating fishing times at inshore fishing places; and making certain that seaweed remained off limits at certain times of the year to preserve it as fish food and thus ensure good shore fishing. The ancient Hawaiians were not only skilled and knowledgeable fishermen, but they also respected the customs and traditions associated with this activity, which was a mainstay of their life. Fishing kapu were considered especially important because they were the method of preserving the harvest of the sea for coming generations, and they were observed with great care. (2) Aquaculture (a) Fishponds i) Origin Anthropologist William Kikuchi has broadly defined Hawaiian aquaculture as "the indigenous, economic, technological and political control of natural pools, ponds, and lakes, and of man-made ponds, enclosures, traps, and dams for the culture and harvest" of various marine resources to ensure year-round food availability. The Hawaiian fishponds comprised an early attempt to prudently manage and control the sea's resources for use by man. Fishponds held and fattened fish captured in the sea and served as a source of fish under kapu during their spawning season. The growing of fish in ponds and their conservation for future needs was an advancement on simply capturing food to fill immediate demands and denotes an increasing awareness of the need to manage food systems as the population expanded. Fish did not spawn in the ponds, however, and the level of stock management in them was very limited. The productivity of these historic Hawaiian fishponds was not great because of limited food availability, inter-species competition, and uncontrollable predation. Fishponds did, however, help provide chiefs and their retinue with much of the large quantity of fish they required. Nowhere else in Polynesia was true aquaculture developed and nowhere else in the Pacific did fishponds exist in the types and numbers found in prehistoric Hawai'i. Where the concept of aquaculture came from and when it was introduced into the Hawaiian Islands is unknown, but it is thought that the idea of fishtraps, probably coming with migrants from the Society Islands, preceded that of fishponds. Probably the earliest aquacultural system in ancient Hawai'i consisted of simple fishtraps, dams, weirs, and natural pools, which were in the hands of the commoners. The Hawaiians ultimately developed the more dependable and efficient ponds. Prehistoric Hawaiian aquaculture encompassed the seven major islands of the group — Ni'ihau, Lana'i, Maui, Kaua'i, O'ahu, Moloka'i, and Hawai'i — but fishponds were particularly extensive on the latter four. Kikuchi states that at least 449 ponds are known to have been constructed prior to A.D. 1830, mostly during prehistoric times in periods of intensification of production to feed large populations. Only on Hawai'i was there an intensive effort to utilize practically every form and body of water for agricultural and aquacultural use. Ancient Hawai'i's broad aquatic food production system, then, included structures built to catch mature fish as well as structures and practices related to true aquaculture. These latter structures existed throughout the islands and included numerous manmade and natural enclosures of water in which fish and other products were raised. Hawaiian tradition associates a large number of ponds with particular chiefs who directed their construction. Based on genealogies, the first true fishponds may have been built as early as the fourteenth century; there are many definite references to their construction throughout the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries. By the end of the eighteenth century, high chiefs are known to have owned more than 300 fishponds. Ownership of one or more fishponds was a symbol of chiefly status and power. According to Apple and Kikuchi, accessibility to some prehistoric fishponds and their products was limited to the elite minority — the chiefs and priests. Because these ponds were kapu to the common majority, they yielded them no direct benefit. Indirectly, however, royal fishponds insured less demand on the commoners' food resources. ii) Types and Construction The extent and distribution of fishponds depended on the local topography. In areas where broad, shallow fringe reefs existed close to shore, numerous ponds could easily be formed by constructing semicircular stone walls arcing from the shoreline. Although Hawai'i Island does not have this type of coastline, it does have many natural ponds in lava basins along the shore; the addition of walls and gates made these operational as fishponds. Loko is the general Hawaiian term for any type of pond or enclosed body of water. The two major categories of loko were shore ponds and inland ponds. Hawaiians recognized five main types of fishponds and fishtraps: loko kuapa, loko pu'uone, loko wai, loko i'a kalo, and loko 'ume'iki (Illustration 6). Ruling chiefs owned the first three types, and perhaps some of the larger and more productive of the other types, because they produced consistently and in sufficient quantity throughout the year to be highly prized. Common people and the konohiki mostly constructed and utilized the inland types, which primarily comprised natural freshwater holding ponds (loko wai) in which fish were placed and allowed to fatten, smaller fishtraps, and small irrigated taro plot ponds (loko i'a kalo), which provided only small and erratic yields. Other inland ponds were much larger, requiring collective labor forces for construction, and were almost exclusively for use by the chiefs.

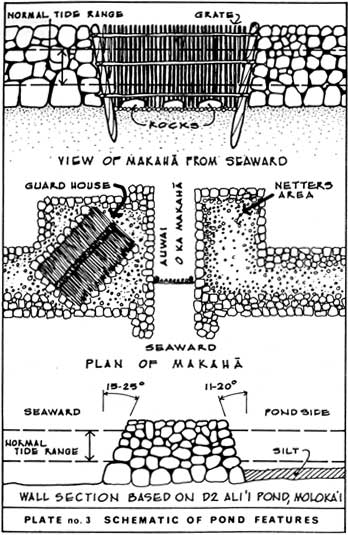

The three royal types of fishponds comprised: loko kuapa, the most important type of shore pond, artificially enclosed by an arc-shaped seawall and containing at least one sluice gate (makaha); loko pu'uone, an isolated shore fishpond containing either brackish or a mixture of brackish and fresh water, formed by development of a barrier beach paralleling the coast, and connected to the ocean by a channel or ditch; and a loko wai, a natural freshwater inland pond. The loko kuapa pond type is unique in Polynesia to the Hawaiian Islands. It was constructed either by building walls in relatively shallow water from two points along the shore into a semi-circular seawall or by constructing a seawall (kuapa) across the opening of a natural embayment. Ponds of this type, built within embayments, occur at several sites along the west coast of the island of Hawai'i. (The loko 'ume'iki [fishtrap] will be discussed later.) Although many different kinds of fish filled these large ponds, the main inhabitants were mullet ('ama'ama) and milkfish (awa). The algae they fed on grew best when sunlight, salt, and fresh water combined in just the right proportions. Therefore, these walled fishponds needed to be shallow, from two to five feet in depth, so that sunlight could penetrate. Some ponds had fresh water springs in them or were located at the mouths of streams so that fresh water could combine with ocean water within its walls. The larger a pond's acreage, the greater the rate of evaporation, and the greater the need for an adequate supply of fresh water that could be diverted into the pond when necessary. Balancing the salinity, the food supply for the fish, the temperature, and other environmental needs was important to the success of the loko kuapa. Materials used in the construction of prehistoric fishponds came from local sources and included stone and coral for the walls; lithified sand, alluvium, and vegetable materials for filling, surfacing, and cordage; and timber for sluice grates. The main seawall of one of these ponds comprised coral boulders or rocks or unworked basalt and ranged in width from three to nineteen feet, five feet being average. They were usually three to five feet high and faced on both sides with block construction. They were always massive and well built compared to secondary and tertiary walls within the confines of some ponds, which probably served to segregate fry from predators. The construction of fishponds involved men standing in a line from the source of the building material to the construction site and passing rocks of huge size along the human chain. Some of the fishponds were massive, their assembly being intensive, lengthy, and costly in terms of material, manpower, and the expense of feeding or housing workers. Grills or grates (makaha) composed of straight sticks tied to one or more crossbeams obstructed the openings through the seawall (Illustration 7). The upright sticks stood close enough together that the sea water and young fry could pass in and out but larger fish could not. The makaha were stationary, with no movable parts, and were sometimes placed across a sluice or ditch, channels formed by two parallel rows of stone walls running into the pond from the grill opening. These sluices carried water into the pond from an agricultural irrigation system or from a river, spring, or the sea, creating a brackish water environment. There are no traditional standard locations for these grates, which were probably placed to provide flow into and out of the pond to reduce silting and inhibit stagnation. This sluice gate, the most distinctive and unique feature of the Hawaiian aquacultural system, was probably the technological innovation that allowed prehistoric Hawaiians to move from high tide-dependent fishtraps and from enclosed ponds with no sea access to artificial estuaries that could be controlled at all times of the tide.